The Mayflower

Photos Bruce Alan St. Germain

Photos The Mayflower Hotel

Its History

The Mayflower Hotel, part of The Autograph Collection, is a capital classic, a landmark hotel that brings timeless elegance, integrity and contemporary style to its role as a vibrant social hub – a Washington, D.C. original since 1925.

The Mayflower Hotel hosted the Inaugural Ball of President Calvin Coolidge just two weeks after its opening. It hosted an Inaugural Ball every four years until it hosted its final ball in January 1981.[92][93] In 1927, Charles Lindbergh was awarded the Hubbard Medal by National Geographic Society, whose headquarters resided one block over from the hotel. A breakfast for 1,000 was held at the hotel.

President-elect Herbert Hoover established his presidential planning team offices in the hotel in January 1928,[94] and his Vice President, Charles Curtis, lived there in one of the hotel's residential guest rooms during his four years in office.[91]

Heads of state met in a private room at The Mayflower in 1929 to foster continuing relations between North and South America. Senator Huey Long also lived at the Mayflower, taking eight suites in the hotel from January 25, 1932, to March 1934.[95][96]

Twice, the Mayflower has been the site where a U.S. presidential campaign was launched, and twice it hosted events which proved to be turning points in a presidential nomination. In March 1931, Franklin D. Roosevelt was vying with Al Smith for the Democratic presidential nomination of 1932. John J. Raskob, chair of the Democratic National Committee (DNC), opposed Roosevelt's candidacy. Knowing that Roosevelt had privately committed to repealing Prohibition but had not done so publicly (leaving him "damp"), Raskob attempted to force the DNC, then meeting at the Mayflower Hotel, to adopt a "wet" (or repeal) plank in the party platform. Instead of drawing Roosevelt out, the maneuver deeply offended Southern "dry" (anti-repeal) Democrats—who abandoned Smith and threw their support to the allegedly more moderate Roosevelt, and helped him secure the nomination.[105][106][107][108]

President-elect Roosevelt spent March 2 and 3 in Suites 776 and 781 at the Mayflower Hotel before his inauguration on March 4.[97][98][i][99] Here on the eve of his inaugural address, with a country facing The Great Depression, President Roosevelt pens one of the most famous lines in U.S. political history, “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.”

Three events of significance during World War II happened at the Mayflower. In June 1942, George John Dasch and seven other spies from Nazi Germany entered the United States after being transported to American shores via a submarine. Their goal, named Operation Pastorius, was to engage in sabotage against key infrastructure. But after encountering a United States Coast Guard patrol moments after landing, Dasch decided the plan was useless. On June 19, 1942, he checked into Room 351 at the Mayflower Hotel and promptly betrayed his comrades.[101][102]

Eighteen months later, a committee of the American Legion met in Room 570 at the Mayflower Hotel from December 15 to 31, 1943, to draft legislation to assist returning military members reintegrate into society. Their proposed legislation, the Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944—known informally as the G.I. Bill—was put into final draft from by Harry W. Colmery on Mayflower Hotel stationery.

First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt took an active role in promoting the sale of savings and war bonds as well as defense stamps. In September 1941, The Mayflower Hotel hosted the retailers for Defense Week and was one of 6,000 hotels across the country to sell the stamps.

The acoustics in The Mayflower’s Chinese Room played a trick on Prime Minister Winston Churchill in 1945. While attending a state dinner, Churchill leaned over to his neighbor to tell him an off-color joke. To Churchill’s surprise, his voice was carried up to the dome and magnified to the horror of two distinguished women and President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who were all seated in the room.

United States Deputy Secretary of the Treasury and former Governor of North Carolina Oliver Max Gardner and his wife, Fay Webb-Gardner, lived at the hotel from 1946 to 1947.[100]. In 1948, President Harry S. Truman told a cheering audience of Young Democrats of America at a dinner at the Mayflower on May 14 that he intended to seek re-election in 1948.[109][110]

In 1947, a major restoration revealed buried treasures that had been lost for decades, such as the hotel’s silver collection pictured. A group of workers came across a locked basement storeroom with valuable gold, silver and cloisonné serving and centerpieces, urns, cases and candelabras worth several thousand dollars each.

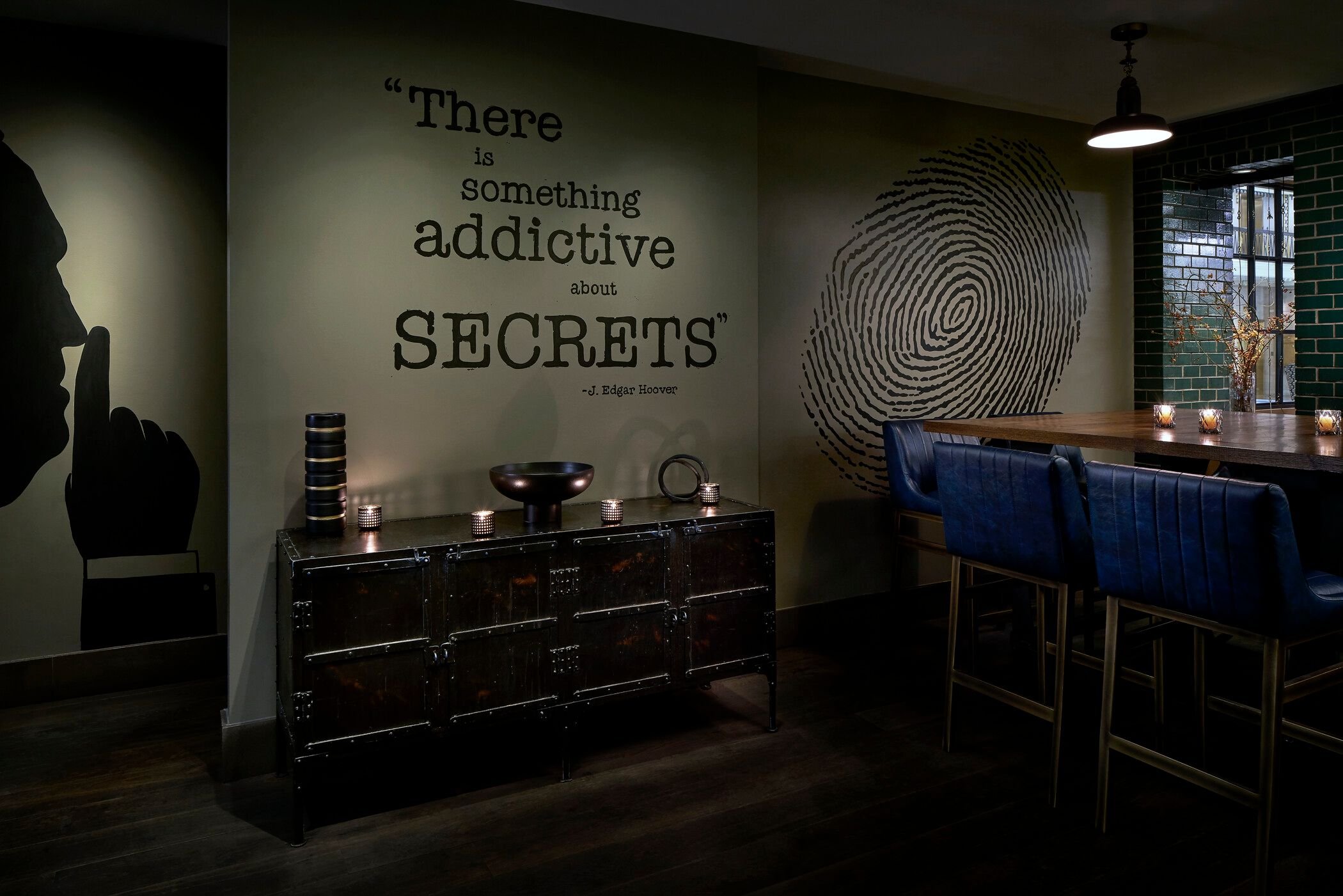

J. Edgar Hoover, director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), lunched nearly every day at the Mayflower Hotel's Rib Room with Clyde Tolson, associate director of the FBI, from 1952 until Hoover's death in 1972.[113][114][115]Hoover had the same lunch every day: chicken soup followed by a salad of iceberg lettuce, grapefruit, and cottage cheese. Buttered white toast was served on the side. (He brought his own diet salad dressing.) Hoover was so well known at the Rib Room that he sometimes ducked out through the kitchen to avoid reporters.[91]

The Mayflower has been in the news several times in relation to political sex scandals. Judith Exner, who claimed to be President John F. Kennedy's mistress, said she stayed in the hotel while in D.C. to secretly meet with the president for sexual trysts.[115] Monica Lewinsky stayed at the Mayflower Hotel when her affair with President Bill Clinton was in the news, and she was extensively interviewed by federal investigators about the scandal in the Presidential Suite.[115][116] The Mayflower was also the location where Lewinsky was photographed with President Clinton at a campaign event not long before the 1996 election; this photograph later became an iconic component of the media coverage of the scandal.[117] On March 10, 2008, The New York Times reported that New York Governor Eliot Spitzer patronized a high class prostitution service called Emperors Club VIP while staying at the Mayflower on February 13.[118] Spitzer allegedly had sex for over two hours with a $1,000-an-hour call girl in room 871 while registered under the alias George Fox.[119]

Ronald Reagan’s former aides and presidential library volunteers gathered in the Cabinet Room in 2004 following his death to prepare and distribute the 1,000 funeral invitations that Nancy Reagan has asked to be sent to family and friends. Former Peace Corps and Office of Economic Opportunity director Sargent Shriver announced his run for President of the United States at the Mayflower on September 20, 1975.[111] Shriver withdrew from the race after a very poor showing, but a more successful campaign began there in 2008. Senator Barack Obama had locked down the 2008 Democratic nomination for President on June 3, 2008. Hillary Clinton conceded the nomination to Obama on June 7, and introduced Obama to about 300 of her leading contributors at a meeting at the Mayflower on June 26, 2008.[112]

Photos Bruce Alan St. Germain

Its Architect

Photo Library Of Congress

Whitney Warren

1864 – 1943

Whitney Warren (January 29, 1864 – January 24, 1943)[1] was an American Beaux-Arts architect who founded, with Charles Delevan Wetmore, Warren and Wetmore in New York City, one of the most prolific and successful architectural practices in the US.

Warren was born in New York City on January 29, 1864. He was one of nine children born to George Henry Warren I and Mary Caroline (Phoenix) Warren .[2] His siblings included Lloyd Warren, who was also an architect,[3] and George Henry Warren II,[4] a stockbroker who was the father of Constance Whitney Warren.[5] He was a cousin of the Goelets[a] and Vanderbilts[b] and the grandson of U.S. Representative Jonas Phillips Phoenix.[7][c]

In 1883, he enrolled at Columbia University to study architecture, but only stayed for one year.[9] He was shown on official Columbia University records as a member of the class of 1885 of the School of Mines, Columbia University.[10][11] From 1884 until 1894, Warren spent ten years at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. There he studied under Honoré Daumet and Charles Girault,[12] and met fellow architecture student Emmanuel Louis Masqueray, who would, in 1897, join the Warren and Wetmore firm.[13]

In 1884, Warren was married to Charlotte Augusta Tooker (1864–1951)[15] in Newport, Rhode Island.[16] Charlotte was the eldest daughter of Gabriel Mead Tooker, a prominent New York lawyer and member of Mrs. Astor's famous Four Hundred.[16]

Warren returned to New York in 1894, and began practicing as an architect.[13] One of his first clients was the lawyer Charles Delevan Wetmore. After their successful collaboration, Warren convinced Wetmore to become his partner and they organized Warren and Wetmore with Warren as the architect and Wetmore responsible for the business side of the firm.[14] Their society connections led to commissions for clubs, private estates, hotels and terminal buildings, including the New York Central office building, the Chelsea docks, the Ritz-Carlton, Biltmore, Commodore, and Ambassador Hotels. They were the preferred architects for Vanderbilt's New York Central Railroad.

During World War I, Warren was involved in organizing the Comité des Étudiants Américains de l'École des Beaux-Arts Paris; a student-run charity in support of the French cause. He also supported actively the claims of Italy in the Adriatic, during and after the war. He was an intimate friend of Gabriele d'Annunzio, and was appointed diplomatic representative in the United States of the "Free State of Fiume". He was the author of Les Justes Revendications de l'Italie: la Question de Trente, de Trieste et de l'Adriatique. Many of his addresses, delivered 1914-1919, were published and widely distributed.[12]

The firm's most important work by far is the construction of Grand Central Terminal in New York City, completed in 1913 in association with Reed and Stem. Warren and Wetmore were involved in a number of related hotels in the surrounding "Terminal City". In 1917, Warren received the Medal of Honor from the American Institute of Architects for the firm's work. Works by Warren are found in the collection of the Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum.[28] Warren took particular pride in his design of the new library building of the Catholic University of Leuven, which was finished in 1928. The library was severely damaged by British and Germain forces during World War II, but was completely restored after the war. [14]

Among the firm's other commissions were:

the Racquet House at the Tuxedo Club, Tuxedo Park, New York, 1890-1900

Newport Country Club, Newport

Newport Country Club, Newport, RI, 1895

Westmorly Court, part of Adams House at Harvard University 1898-1902

New York Yacht Club, 1899

High Tide, William S. Miller residence, Newport, RI 1900

10 West 56th Street, the Edey Mansion, 1901

Kirby Hill Estate (Eric Kuvykin Mansion), Long Island, New York, 1902

the Marshall Orme Wilson House, 1903

the Brooklyn Department of Street Cleaning's Stable and Chateau, Brooklyn, New York, 1904

49 East 52nd Street, Vanderbilt guest house, New York City, 1908

Green-Wood Cemetery Chapel, New York City, 1911

Union Station, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, 1911

Union Station, Houston, Texas, 1911 (Now a part of Minute Maid Park)

Aeolian Hall, 1912

Ritz-Carlton, Montreal, Quebec, 1912

The Pantlind Hotel, now the Amway Grand Plaza Hotel, Grand Rapids, Michigan, 1913

Grand Central Palace, New York City, 1913 with Reed and Stem, demolished 1964[2]

Michigan Central Station, Detroit

The unfinished Michigan Central Station, Detroit, Michigan, 1913, also with Reed and Stem

Ritz-Carlton, Philadelphia, PA, 1913, with Horace Trumbauer

Packard Manor, Chautauqua, New York- A summer home for William Doud Packard, 1915

the Texas Company, Texaco Building, Houston, Texas, 1915

New York Central Railroad Station, 1 East Hartsdale Avenue, Hartsdale, New York

927 Fifth Avenue, New York City, a cooperative apartment house, 1917

The Broadmoor Hotel, Colorado Springs, 1918

The Ambassador Hotel, Atlantic City, 1919

Struthers Library Building, Warren, Pennsylvania, renovations, 1919

The Commodore Hotel, now the Grand Hyatt New York, part of "Terminal City", 1920

The New York Biltmore Hotel, also part of "Terminal City"

Crown Building, formerly the Heckscher Building, New York City, 1921

The Briarcliffe, 57th Street, New York City

Ritz-Carlton, Atlantic City, NJ, 1921

Providence Biltmore Hotel, Providence, Rhode Island, 1922

Mayflower Hotel, Washington, D.C., 1922, with Robert F. Beresford

Asbury Park Convention Hall, 1923, and the adjoining Paramount Theatre, 1930

Madison Belmont Building at Madison Avenue and 34th Street, New York City, 1925

Steinway Hall at 111 West 57th Street, New York City, 1925

Italian Embassy building, Washington DC, 1925

200 Madison Avenue, New York City, 1926

Royal Hawaiian Hotel, Honolulu, Hawaii, 1927

689 Fifth Avenue, New York City, 1927

St. James Theatre, New York City, 1927[4]

Consolidated Edison Building at 4 Irving Place in Manhattan, 1928

Norwood Gardens terrace homes, 36th St., Astoria, New York, planned development by W&W architect Walter Hopkins, 1928

The Helmsley Building, originally the New York Central Building, part of the Grand Central Terminal complex, 1929

Empire Trust Company Building, 580 Fifth Avenue, New York; currently the World Diamond Building as of 2013

the Chelsea Piers

903 Park Avenue, a Bing & Bing building.

In 1927, Warren and his brother George each inherited $2,314,143 from the estate of their uncle, Lloyd Phoenix.[1] Warren retired in 1931, but occasionally served as consultant.

Warren died after a nine-week illness on January 24, 1943 at New York Hospital in New York City.[1] At the time of his death, Warren resided at 280 Park Avenue in New York City and was a member of the Knickerbocker Club, the Racquet and Tennis Club, and the Church and South Side Sportsmen's Clubs.[1] After a service at St. Thomas Church, he was buried at Island Cemetery in Newport.[27] His widow died in 1951 and was buried alongside him in Newport.[15]

Photos Bruce Alan St. Germain And The Mayflower Hotel

Indiana limestone would be used for the facade on the first three floors, with rusticated brick and terra cotta trim on all upper floors.

Rustication is a range of masonry techniques used in classical architecture giving visible surfaces a finish texture that contrasts with smooth, squared-block masonry called ashlar. The visible face of each individual block is cut back around the edges to make its size and placing very clear. In addition the central part of the face of each block may be given a deliberately rough or patterned surface.

Architectural terracotta refers to a fired mixture of clay and water that can be used in a non-structural, semi-structural, or structural capacity on the exterior or interior of a building. Terracotta pottery, as earthenware is called when not used for vessels, is an ancient building material that translates from Latin as "baked earth".

Its Architectural History

Today, a four-star hotel[7], the Mayflower Hotel is managed by the Autograph Collection Hotels division of Marriott International. The Mayflower is the largest luxury hotel in the District of Columbia, the longest continuously operating hotel in the Washington D.C. area, and a rival of the nearby Willard InterContinental and Hay-Adams Hotels. The Mayflower is known as the "Grande Dame of Washington",[4] the "Hotel of Presidents",[5] and by many as the city's "Second Best Address" (the White House is the first)—the latter sobriquet attributed to President Harry S. Truman (a frequent guest at the hotel).[6]

The site on which the Mayflower Hotel sits was, after the organization of the District of Columbia in 1792, initially owned by the federal government who sold the property to Nathaniel Carusi for $5,089. Carusi sold the site to the Order of the Visitation of Holy Mary in 1867 for $50,000.[8][a] The order built the Convent of the Visitation on the site, a structure that occupied the land until the construction of the Mayflower Hotel itself.[9]

The Mayflower Hotel was built by Allan E. Walker, the land developer behind Brookland and other residential neighborhoods of Washington.[10] Initially called the Hotel Walker, it was to have 11 stories, 1,100 rooms, and cost $6.2 million ($100,370,974 in 2021 dollars).[11] On May 27, 1922, the Walker Hotel Company was organized, with Allan Walker as president. The corporation issued 80,000 shares of preferred stock worth $2 million and 80,000 shares of common stock, and purchased a site on the north half of the block on DeSales Street between 17th Street and Connecticut Avenue.

Plans for the hotel, whose cost was now pegged at $6.75 million ($109,274,851 in 2021 dollars), now included an 11-story, 1,100-room hotel facing Connecticut Avenue, whose first two floors would be common rooms, and an eight-story residential hotel facing 17th Street. Robert F. Beresford of Washington, D.C., and the New York City architectural firm of Warren and Wetmore were appointed the architectsd. Beresford said the structure would be built of concrete and brick around a steel frame. Indiana limestone would be used for the facade on the first three floors, with rusticated brick and terra cotta trim on all upper floors.[12] By June 6, however, the cost of the hotel had risen to $8 million ($123,612,903 in 2021 dollars),[13][10] largely due to a sizeable expansion in the size of the ballrooms (the largest of which could now seat 1,600 people),[14] meeting rooms, and other public spaces on the first two floors and first basement level.[13]

Construction costs continued to rise, however. Although scheduled to open January 1, 1924,[17] the hotel remained unfinished. The Allan E. Walker Investment Company, the largest shareholder in the Hotel Walker Company began running short of funds, slowing construction. Nearing bankruptcy, the Walker Investment sold its interest in the Hotel Walker to C.C. Mitchell & Company, builder of large apartment complexes and hotels in Boston and Detroit. The reported price of the sale was $5.7 million for the $8.5 million hotel.[14] But in fact, costs had risen much higher, and the hotel's final cost was closer to $11 million ($169,967,742 in 2021 dollars). The new owners changed the name to the Mayflower Hotel in honor of the 300th anniversary of the landing of the Mayflower and the Pilgrims at Plymouth Rock.[15]

The Mayflower Hotel opened on February 18, 1925.[15][b][18] The hotel sat on 1.5 acres (6,100 m2) of land, and had roughly 100,000 square feet (9,300 m2) of interior space.[9] Several heating oil furnaces and one of the world's largest air conditioning units kept the hotel at an even 70 °F (21 °C) year round.[c][9] The hotel's promenade, as completed, was 26 feet (7.9 m) wide and 300 feet (91 m) long.[14][d][9][19]

The Mayflower Hotel's interior design was created by E. S. Bullock of Albert Pick & Co.[9] The furnishings, which cost $1.25 million ($15,837,903 in 2021 dollars), were antique and reproduction pieces in the Sheraton, Louis Quinze, and early Renaissance styles.[20] "Walls, floors, stairs, pilasters and wainscoting in the lobby and the major function rooms [were] clad in a wide array of American and imported marbles, and ceilings and walls throughout the first floor and mezzanine [were] ornamented by finely cast, low-relief plaster decorations, often further embellished with gold leaf."[26]

The use of gold gilt to trim decoration was extensive; newspapers said the hotel contained more gold trim than any other building except the Library of Congress.[27] Original artworks, some by quite famous artists, adorned the public spaces. These included four larger-than-life-sized portraits of the first four presidents by painter and muralist Louis Grell of Chicago.[28] Three marble statuary groups were also displayed in the lobby and public areas: La Sirene by Denys Puech; Flora by William Couper; and The Lost Pleiad (also known as Merope Married a Mortal) by Randolph Rogers. Two smaller pieces by Rogers, Nydia, the Blind Girl of Pompeii and Boy and Dog, were also on display.[9]

The Mayflower Hotel offered guests amenities unparalleled among hotels in the United States. This included air conditioning in all the public rooms (the first time a hotel had used air conditioning on such a large scale), and ice water and fans in all guest rooms. Services included daily maid service, a laundry, a barber shop, a beauty salon, a garage for automobiles, a telephone switchboard, and a small hospital staffed by a doctor.[5]

The hotel had 440 guest rooms,[5] each with its own shower bath. Guest suites had a sitting room, dining room, bath, and up to seven bedrooms.[9] The hotel's 500 residential guest apartments each had its own kitchenette, dining room, and drawing room with fireplace.[9][20] Some had as many as 11 rooms, and up to five baths.[20]

The cruciform lobby had a mezzanine on the north, west, and south sides, and marble-clad piers divided the north and south walls into three bays. A small cocktail lounge was located along the north wall, while the reception desk occupied the south wall.[21] The lobby received light from a coffered skylight. Four great bronze torchères, hand-wrought and trimmed with gold, dominated the lobby (and were claimed by the hotel to be "priceless").[22] In the hotel's early years, the lobby skylight was painted over.[21]

The main lobby entrance on Connecticut Avenue had a stairway that led down to the first below-ground level, where public restrooms, the barber shop, and a shoeshine stand (made of marble) were located. A secondary corridor and steps behind the elevators led to the Presidential Room; another secondary corridor to the east of the front desk led to the Mayflower Coffee Shop. The four elevators to the east of the lobby, joining it to the Promenade, had bronze doors with images of the Mayflower vessel on them.[21]

The Mayflower featured three restaurants. The 66 by 76 feet (20 by 23 m) Palm Court featured a glass dome supported by iron latticework, numerous palm trees, and a marble fountain and pool with water lilies growing in it.[23] The 50 by 169 feet (15 by 52 m) Presidential Restaurant[19] was decorated with the seals of the Thirteen Colonies.[9] Both were located on the main floor. Early in World War II, the skylight in the Palm Court was covered over with a mural painting. The skylight was later flocked with pieces of velvet.[45]

The Garden Terrace was located on the first below-ground floor.[19] The Italianate style[9] room featured a coffered ceiling done in copper, a marble fountain, plaster walls in warm pastel tints, alcoves designed to look like arbors, and murals of early Washington, D.C., and nearby Mount Vernon.[19] Two well-known hoteliers managed the restaurants: Jules Venice, the maitre d'hotel, and Sabatini, former chef at Delmonico's.[9]

The hotel's Grand Ballroom featured a stage with proscenium,[9] beneath which was a hidden thrust stage that could be projected out into the ballroom.[24] The Grand Ballroom's main entrance was on 17th Street, where a covered, semi-circular carriageway allowed up to three carriages at a time to unload patrons. The hotel also had several small, private ballrooms for more intimate events.[9] Next to the ballroom on the 17th Street side was the Chinese Room—a sumptuous meeting and banqueting room inspired by The Peacock Room by James McNeill Whistler.[15][e][25]

With the Mayflower Hotel finished but not yet furnished in September 1924,[14] plans were made to enlarge the structure even before it opened. The new owners perceived high demand for guest room suites, and quickly designed a $1 million ($15,451,613 in 2021 dollars) addition.[29][30] Construction began in October 1925, and within six weeks the 40-foot (12 m) deep foundation had been dug.[31] The addition opened on May 31, 1925.[30][31]

The most prominent features of the Annex were the Presidential Suite and the Vice Presidential Suite. The Presidential Suite occupied the 10th floor, and was decorated in green and gold in the Italianate style. The Vice Presidential Suite occupied the ninth floor, and was decorated in dull and bright yellow in the Louis XVI style.[31] Each suite had 13 rooms,[30][31] which included a foyer, drawing room, library, secretary's room, dining room, and five bedrooms—each with its own bath and kitchenette.[31] Each suite also had a maid's room, with an attached bath.[32]

The furnishings of both suites were copies of museum pieces. The Presidential Suite featured a marquetry table with ormolu fittings; a Louis XVI cabinet with painted panels; Oriental rugs; bronze and marble urns in the Neoclassical style; drapes of silk damask; and underdrapes of silk taffeta. The suite's dining room featured Queen Anne style furniture. The Vice Presidential Suite featured a dining room with furniture in the Sheraton and Hepplewhite styles. Dining room furniture in both suites was manufactured from satin-walnut, and featured painted decorations and marquetry. The bedrooms in both suites featured Louis XVI-, Adam-, and Federal-style furniture made of satinwood, walnut, and mahogany. Each piece was painted, lacquered, or marquetried.

Dust-covers for the beds were also of taffeta. Sofas and chairs in each suite were upholstered in imported brocades, while the walls were covered in hand-made tapestries. Each suite had numerous shaded lamps, porcelain and crystal art objects, and gilt mirrors. Original oil and watercolor paintings as well as etchings and engravings—many of them by famous artists—decorated the suites. Each suite's bathroom was completely tiled in white, with silver-plated fixtures for the sink and shower, an engraved glass shower door, and a Swiss shower.[31][f][33] The kitchens, too, were tiled in white, and contained an electric stove and oven, a Frigidaire refrigerator, silver tableware, complete porcelain table setting, and fine table linens.[31]

The second through eighth floors of the Annex contained guest suites. Each suite had five bedrooms, and each bedroom had its own bath. The first floor of the Annex was occupied by the Mayflower Coffee Shop, a vastly expanded version of the highly popular but extremely small café located on the ground floor of the existing hotel.[31] The basement of the Annex occupied by a huge laundry, which served the hotel and annex.[30][31]

Walls, floors, stairs, pilasters and wainscoting in the lobby and the major function rooms were clad in a wide array of American and imported marbles, and ceilings and walls throughout the first floor and mezzanine were ornamented by finely cast, low-relief plaster decorations, often further embellished with gold leaf.

The term relief refers to a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces are bonded to a solid background of the same material. There are different degrees of relief depending on the degree of projection of the sculpted form from the field, for which the Italian and French terms are still sometimes used in English. The full range includes high relief (alto-rilievo, haut-relief), where more than 50% of the depth is shown and there may be undercut areas, mid-relief (mezzo-rilievo), low relief (basso-rilievo), or French: bas-relief, and shallow-relief or rilievo schiacciato, where the plane is only very slightly lower than the sculpted elements. There is also sunk relief, which was mainly restricted to Ancient Egypt.

The use of gold gilt to trim decoration was extensive; newspapers said the hotel contained more gold trim than any other building except the Library of Congress.

The Great Depression had a significant impact on the Mayflower Hotel. It lost money (as much as $760,000 over two years), and in 1929 its affairs were placed in the hands of a special committee established by American Bond & Mortgage. The hotel continued to lose money, and on May 22, 1931, holders of the hotel's original bonds secured a ruling that the hotel was bankrupt.[35] American Bond was declared bankrupt the same day.[36] The receivers later alleged that the hotel had lost more than $2 million since it opened, and that American Bond had issued a large amount of bonds with the hotel as security (worsening the hotel's financial status).[34] American Bond won dismissal of the bankruptcy ruling on June 26,[37] A second bankruptcy was declared by the court on July 28, 1931.[38] Fraud charges were later levied against officials of American Bond & Mortgage.[39] American Bond finally admitted the hotel was bankrupt in October 1931.[40]

Holders of the second bonds (issued with the hotel as security), however, feared that they would receive nothing if the Mayflower were foreclosed. They petitioned a court to remove the receivers and to appoint new trustees who would sell the hotel. The court agreed, and the sale began to move forward in 1933.[41] Concerned about the sale, Senators Hamilton Fish Kean and Robert Rice Reynolds began an investigation into the bankruptcy and sale. In 1933, Kean and Reynolds won congressional approval in June 1934 for the Corporate Bankruptcy Act, which allowed the Mayflower Hotel itself to declare bankruptcy and refinance itself.[42] With the receivers having made the hotel profitable once more,[43] the hotel reorganized its finances in a court-approval bankruptcy proceeding on December 20, 1934.[44]

In December 1946, Hilton Hotels Corporation purchased the Mayflower Hotel for $2.6 million.[46] Some of the Mayflower's stockholders challenged the sale, arguing the price was too low. A court dismissed the suit in May 1947.[47] Over the next decade, Hilton Hotels spent about $1 million refurbishing the guest rooms a nd public spaces.[48] Hilton Hotels purchased the Statler Hotels chain in 1954, and as a result owned multiple large hotels in many major cities, as in Washington, where they now owned the Mayflower and the Statler Hotel. Soon after, the federal government filed an antitrust action against Hilton. To resolve the suit, Hilton agreed to sell a number of their hotels, including the Mayflower Hotel.[49]

Hilton Hotels sold the Mayflower to the Hotel Corporation of America (HCA) on April 1, 1956, for $12.8 million.[48] HCA renovated the Mayflower's old Garden Terrace, renaming it the Rib Room.[50] The hotel's occupancy rates were lower than average, however. In 1963, for example, the Mayflower lost $450,000.[51] HCA privately expressed interest in selling the property.

On October 28, 1965, the locally owned May-Wash Associates offered to buy the Mayflower for $14 million.[49] May-Wash Associates consisted of William Cohen, a local real estate developer and banker who owned 50 percent of the company; Kingdon Gould Jr. and his son, Kingdon Gould III, local real estate developers who owned 35 percent; Ulysses "Blackie" Augur, a local restaurateur who owned 10 percent; and Dominic F. Antonelli, owner of a string of parking lots in the area who owned 1 percent.[52] HCA's board of directors approved the deal on November 11, 1965. HCA continued to manage the hotel for the new owners.[53]

The Mayflower Hotel underwent a $2.5 million refurbishment of its common rooms in 1966 and 1967.[54] The renovation got rid of the Presidential Restaurant and renamed it Le Chatelaine.[55] HCA was renamed Sonesta Hotels in 1970.[56]

May-Wash Associates considered closing the Mayflower Hotel in 1971 after it lost $485,000 the previous year. Lead May-Wash investor William Cohen said that if Congress weakened the restrictions of the Height of Buildings Act of 1910, the company would tear down the Mayflower and erect a 20-story office and retail skyscraper with 500,000 square feet (46,000 m2) of office space and 250,000 square feet (23,000 m2) of retail space. If the Height Act remained in force, Cohen said the hotel's first two floors would be transformed into a shopping mall accommodating 40 to 50 small businesses.[51] But the plan was abandoned later that fall when the Mayflower announced a five-year, $2.5 million renovation that would refurbish the retail stores on the Connecticut Avenue side of the structure. Then on November 1, 1971, May-Wash hired Western International Hotels to manage the property.[57]

Western International said it would invest $500,000 immediately to upgrade guest rooms (which included color television sets for the first time). Western International said the previously announced $2.5 million refurbishment would go to additional guest room renovations, and improvements to dining spaces, banqueting facilities, and ballrooms.[58] The Rib Room lost its name (which had been trademarked by HCA, the previous manager), the facade was cleaned, and the air conditioning repaired and upgraded.[59]

Beginning in April 1973, the Mayflower Hotel served as the temporary Embassy of China in Washington, D.C., for a time while their new embassy building at 2300 Connecticut Avenue NW was being renovated following the re-establishment of diplomatic relations between the United States and the People's Republic of China.[60]

With the Mayflower making a profit, May-Wash Associates undertook at $2.5 million general refurbishment of the guest rooms about 1977. The hotel then announced a $25 million expansion of the hotel in January 1979. The company intended to combine 800 smaller guest rooms in its eastern half into 407 luxury suites, and to add a health club (with racquetball court, sauna, and swimming pool) and café to the 17th Street side of the hotel. Meeting and private dining room space would be added to the structure; all plumbing and mechanical systems would be upgraded; and central air conditioning would replace the window units now in operation.

May-Wash hired architect Vlastimil Koubek to design two new floors to add to the top of the eastern tower, bringing it to the same height as the western tower. The 448 rooms in the hotel's eastern half would be turned into retail space on the two first floors with office space above.[52] The hotel sought to permanently narrow De Sales Street NW as part of its renovations.[61]

Western International Hotels, which managed the property, was renamed Westin Hotels & Resorts in January 1981. In October 1981, May-Wash Associates announced that Stouffer Corp., a division of Nestlé, was taking a minority interest in the Mayflower Hotel, and would assume management of the property on December 1, 1981, under a 20-year agreement. Stouffer said the hotel would be its American "flagship", and the hotel was renamed the Stouffer Mayflower Hotel.[62]

While renovation of the eastern tower proceeded, plans for the western tower drastically changed. The Mayflower abandoned its plan to convert the tower into office space, and instead upgraded the hotel rooms in the eastern tower. In some cases, rooms were merged to create luxury suites. The change in renovation plans left the Mayflower with just 727 rooms, but added 18,000 square feet (1,700 m2) of meeting room space and a new restaurant.[62] The hotel still attempted to narrow DeSales Street NW, proposing to use the extra space to build an enclosed outdoor café (something city laws did not permit).[g][63]

Even as the first renovations were ending, the Mayflower Hotel embarked on another major set of refurbishments and upgrades. This project, which began in 1981 and lasted three years, cost $65 million. The hotel remained open as the project moved forward in phases.[64] In 1981, two floors were finally added to the eastern wing of the structure. The meeting rooms on the hotel's second floor and the Board Room were refurbished, and offices on the mezzanine were removed and the space restored to public use.

The following year, 200 suites received major makeovers, including the installation of baths clad in Italian marble. The Presidential Restaurant was divided into two new banqueting halls, the East Room and the State Room, and the Grand Ballroom and the Chinese Room were renovated. The restoration of the lobby and upgrading of the hotel's restaurants occurred in 1983. Artisans and technicians helped to restore the bas-relief plaster moldings and brass fixtures, clean and restore the hotel's many crystal chandeliers, and apply new gold leaf to areas where the gilt had been damaged or removed. The renovations left the hotel with 721 guest rooms (about half rebuilt and restored) and two restaurants.[65]

The renovation uncovered many historic decorative elements which had been covered up over time. The skylight in the Presidential Room (formerly the Palm Court) was uncovered.[65] When renovation of the former Palm Court began, two previously unknown murals by Edward Laning were discovered.[45] The murals were dated by art experts to 1957,[45] when the Palm Court was radically reconfigured into the Le Chatelaine restaurant.[66] The murals, 25 feet (7.6 m) long and 14 feet (4.3 m) high, depicted Italian formal gardens. They were hidden behind a false wall when the restaurant was turned into meeting room space in early 1978.[45] Discovered in storage were 24 fire-gilded 19th century service platters purchased from the estate of heiress Evalyn Walsh McLean in 1947.[67]

After managing the hotel for ten years, Stouffer bought it outright from May-Wash in 1991 for just over $100 million.[68] In April 1993, Stouffer Hotels was sold by Nestlé to New World Development Company of Hong Kong. Nestlé also gave New World the right to use the Stouffer brand name for 3 years, from 1993 to May 1996. New World already owned the Renaissance Hotels chain, and merged the Stouffer-branded Hotels into it. The Mayflower was renamed the Stouffer Renaissance Mayflower Hotel.[69] In early 1996, the Stouffer branding was retired, and the hotel became the Renaissance Mayflower Hotel.[70] Marriott International bought Renaissance Hotels from New World in February 1997.[71]

Marriott sold The Mayflower to Walton Street Capital in 2005, in a package with seven other Marriott hotels, for a total of $578 million.[72] Walton Street resold the Mayflower to Rockwood Capital in 2007[73] for $260 million, financed with a $200 million securitized loan.[74]

The hotel, appraised at $285 million in 2008, fell in value to $160 million by 2010. With Rockwood's loan over-leveraged, they refinanced the hotel in 2015, with a $160 million loan from Apollo Commercial Real Estate Finance Inc. and other lenders. Also in 2015, Rockwood sold off 71 of the hotel's rooms to Marriott for $32 million, for use by the company's Marriott Vacation Club Destinations time-share division.[1]

In May 2015, the hotel switched from Marriott's Renaissance Hotels brand to Marriott's Autograph Collection brand, dropping the word "Renaissance" from its name. The move was prompted by studies which showed that younger travelers were not brand-loyal and instead looked for individuality and uniqueness when shopping for a hotel stay. Marriott also learned that few travelers knew the Mayflower was a Renaissance Hotel, which made the branding superfluous.[3]

The hotel's Grand Ballroom featured a stage with proscenium, beneath which was a hidden thrust stage that could be projected out into the ballroom. A proscenium is the metaphorical vertical plane of space in a theatre, usually surrounded on the top and sides by a physical proscenium arch (whether or not truly "arched") and on the bottom by the stage floor itself, which serves as the frame into which the audience observes from a more or less unified angle the events taking place upon the stage during a theatrical performance.

Square piers formed colonnades along the north and south walls. Ionic capitals featuring satanic faces topped each pier.

Delicate, bas-relief gilt plaster decorations covered the piers, walls, and ceiling.

A $20 million refurbishment of all rooms and the creation of a club level was completed in August 2015. Each floor of the hotel was given a theme corresponding to a decade, with the second floor devoted to the 1920s, third floor to the 1930s, and so on to the tenth floor. Each room received updated, modern furniture, and the hallways were wallpapered in grey and white with a pattern reminiscent of the lobby mezzanine railing. Each of the hotel's presidential suites also received a complete makeover, and now have a separate office. Rooms on the seventh floor were eliminated to make space for the Marriott Vacation Club Pulse. This left the Mayflower with a total of 581 rooms (512 guest rooms, 67 suites, and two presidential suites). At the completion of the room renovation, the Mayflower announced it would begin a major refurbishment of the hotel's ballrooms and meeting space in late 2016.[75]

In July 2021, Apollo Commercial Real Estate Finance Inc., having already provided Rockwood financing for the 2015 refinancing, bought out Rockwood's share of the hotel, for $86 million.[1]

The lobby originally featured a small store and cocktail bar in its northwest corner.[76] The main entrance to this space was at the corner where the two diagonal walls of the hotel met at the corner of Connecticut Avenue and DeSales Street. In March 1948, the retail area was taken over by the hotel and expanded into a much larger bar and dining space named the Town and Country Lounge.[76] Over the next four decades, the bar became a favorite of Washington politicians and power-brokers. The Sunday Times of London rated Town and Country as one of the "star bars" of the world (alongside the Polo Lounge at the Beverly Hills Hotel in Beverly Hills, California; the mob-constructed lobby bar of the Hotel Nacional de Cuba in Havana, Cuba; and Harry's New York Bar in Paris, France).[77]

The lobby mezzanine was closed off to create office space in 1962.[21][65] The ceiling of the elevator foyer was lowered, which covered up a bas-relief plaster sculpture on the architrave above the east entrance to the elevator foyer and a sunburst medallion on the ceiling of the elevator foyer were both covered over (but not removed). Intricate plaster capitals on the piers in the lobby were also removed at this time. At some point, a door was cut through the curved wall opposite the elevator bank.[21]

The offices were removed from the lobby mezzanine in the 1981–1984 renovation, and the mezzanine restored to its original function.[65] The door in the curved wall opposite the elevators was also sealed.[21]

The Town and Country Lounge was slightly renovated in 2010, with hardwood floors replacing the carpet.[77] The bar's future, however, was not secure. In January 2011, the hotel's lobby, restaurant, bar, and retail spaces[78] underwent a six-month, $5 million renovation (their first since the 1981–1984 refurbishment).[77] The Town and Country Lounge ceased to exist, and the Thomas Pink luxury men's clothing store moved into the space.[78] Thomas Pink had formerly occupied the site of the old Mayflower Coffee Shop on the south side of the lobby. Offices near this space were removed to provide expansion of the space, and a new restaurant to be named EDGAR Bar + Lounge. The lobby itself underwent additional restoration, overseen by the architectural firm of Jonathan Nehmer & Associates,[78] which flipped the lobby orientation.[75]

The Presidential Room was originally decorated in the Adams style.[79] The floor of the room was white Vermont marble tile. Thin diagonal lines of verd antique ran across the floor. Around the floor was an inner, narrow border of verd antique, with a 3-foot (0.91 m) wide border of blue-veined white Pavonazzo marble.[80] Seven square piers, with Doric capitals and gilt festoons, created a narrow colonnade along the north and south walls. A wainscot 4 feet (1.2 m) high, made of white Sylacauga marble with a verd antique baseboard, was placed on the walls and around all the piers. An acanthus crown molding topped the room, and gilt plaster moldings in the shape of finials surrounded each window and doorway. Turned wood spindles decorated the northern wall. The crests of the 13 Colonies, in gilt and polychrome, lined the walls as decorative elements. On the south side of the room, there was a "service pavilion" 7 feet (2.1 m) wide and one story high. A narrow set of stairs gave access to the top of the service pavilion, which was enclosed by a decorative iron railing.[79] The ceiling of the room was decoration with Adams style bas-relief plaster moldings. The center of the ceiling was a long rectangle stretching nearly the long length of the room, surrounded by gilt plaster wreath moldings. A gilt chandelier with silk shades hung from the center of the room. Shallow, circular domes surrounded by gilt plaster wreath moldings existed at the east and west ends of the room. In the center of each dome was a delicate grating, from which hung two more gilt chandeliers with silk shades.[80]

At some point in time, the stairs leading to the top of the service pavilion were removed. The structure was clad in mirrors separated by narrow pilasters, and most (but not all) of the spindles removed from the north wall.[79]

The old Presidential Room was partitioned in the 1981–1984 renovation, and two ballrooms/meeting rooms—the State Room and the East Room—were created out of the space. A removable metal partition was installed to divide the room as well as the service pavilion.[80] Almost none of the other original decorations of the room have been changed since its 1925 creation, however.[79]

The north wall of the Palm Court originally consisted of structural piers, leaving the room open to the Promenade. Pilasters along the south wall mimicked this look and gave the room an aesthetic symmetry. A bay in the east wall was framed by columns and an arch, and an oriel balcony on the mezzanine level projected into the room. At some point in time, the windows in the east wall were filled in, and mirrors inserted in the new, false casements.[83] The Palm Court had a floor of American travertine, a maple dance floor, wainscoting of gold-veined St. Genevieve marble, and intricate plaster moldings on entablature and ceiling.[79]

Walls were added between the piers in 1934, and the Palm Court was internally partitioned in 1947. In 1950, arches were constructed between the piers of the north wall and the pilasters of the south wall in an attempt to connect the walls visually. In 1957, the Palm Court was radically renovated. Its Victorian ironwork was removed and a Neoclassical style decorating scheme implemented.[79] Two large murals by painter Edward Laning were added,[45] and framed with nonstructural columns in an attempt to simulate the vista from a verandah. The room's eastern bay was sealed off, and small staging vestibules added to the south wall, leaving the room strongly asymmetrical.[79]

During the 1981–1984 renovation, the east bay was reopened.[79] The old Palm Court was now confusingly renamed the Presidential Room.

The Promenade[h] originally featured pilasters that defined six bays along both its north and south sides. The capital of each pilaster was decorated with the profile of a different mythological hero, and festooned with swag.[80] Each pilaster had a faux pedestal made of verd antique decorated with plaster rosettes and gilt plaster wreaths.[81] The wainscoting was 3 feet (0.91 m) high, and of white Alabama marble. A baseboard of verd antique and a gray marble dado rail completed the wainscot, and a gilt plaster acanthus crown molding decorated the ceiling.

Arches in the north wall gave access to meeting rooms. The arches leading to the Grand Ballroom, Chinese Room, and the original Presidential Room were topped with sculpted architraves of white Alabama marble, while the other arches were each topped by a gilt plaster crest. At some point in time, the arches which led to the small meeting rooms along the north wall were filled in with gilt-edged mirrors.[80] Beveled mirrors stood between the pilasters.[80] The ceiling of the Promenade consisted of octagonal coffers alternating with small square coffers. At the center of each square coffer was a gilt plaster rosette.[82] The floor was of white Vermont marble and verd antique marble, with a border of verd antique.[81] Architect Shirley Maxwell has noted that the Mayflower's "block-long long lobby and promenade form what is probably the grandest indoor 'street' in Washington..."[32]

The Grand Ballroom was the most opulent room in the Mayflower Hotel. As with the Presidential Room, square piers formed colonnades along the north and south walls. Ionic capitals featuring satanic faces topped each pier.[81] A stage with a proscenium arch was located on the west end.[9] Mirrored French Doors formed the Grand Ballroom's east wall. These could be opened to provide access to the Chinese Room beyond. A small curved balcony, reached by narrow stairs in the northeast and southeast corners of the ballroom, projected over the French doors. The wainscoting was of tan St. Genevieve marble. Six doors pierced the north wall and led to the Promenade, with the end doors reached by curving steps. The floor consisted of a wooden floor with a border of marble. Delicate, bas-relief gilt plaster decorations covered the piers, walls, and ceiling.[81]

The Chinese Room had a square floorplan. A flight of short steps led to the entrance, which was in the curved, north wall. Large, rectangular piers framed an alcove (which ran nearly the depth of the room) on the east.[81] The hardwood floor featured a baseboard of verd antique, and a crown molding of gilt plaster acanthus leaves surrounds the ceiling. The ceiling of the Chinese Room consists of a dramatic elliptical dome. A gilt plaster molding of wreathes surrounds the dome, while the rest of the ceiling is covered in chinoiserie paintings of animals, people, and trees. A two-tiered crystal chandelier hung from the center of the dome.[83]

The Garden Terrace (Originally Named), located on the first below-ground floor,[19] featured Italianate[9] decor, a coffered copper ceiling, a marble fountain, plaster walls in warm pastel tints, alcoves designed to look like arbors, and murals of early Washington, D.C., and nearby Mount Vernon.[19]

The Garden Terrace was radically redecorated in September 1940, and its name changed to the Sapphire Room.[84] Designed by Robert F. Beresford, one of the hotel's original architects, the rear of the room's stage was clad in glowing sapphire-blue glass brick. The overhead arches were clad in aluminum, most of the decoration in the room removed, and the remaining surfaces painted bright blue. Carpet with a brick-like pattern in blue covered the floor.[85]

In about 1950, the Sapphire Room was redecorated in the Colonial Revival style, a popular at the time, and renamed the Williamsburg Room.[85] It was open by at least October 1950.[86] The alcoves were removed and replaced with a raised terrace on the north, east, and south sides of the room. A railing with an oak handrail and turned-wood balusters enclosed the gallery, and a shallow concave stage was added to the west wall. Pilasters, paneled in warm-colored wood, were added to the walls. A wainscot and dado rail of wood covered the lower part of the walls. A highly intricate plaster architrave and broken pediment surmounted the entrances to the terrace.[83] The Williamsburg Room became the Colonial Room about January 1971.[87]

The Mayflower Coffee Shop originally occupied a small space south and slightly west of the main desk and front office on the west side of the hotel. This space was quite small, but was vastly expanded in April 1925 with the completion of the Annex. A soda fountain and candy shop occupied the old coffee shop space, while the coffee shop expanded into a much larger space south of the lobby/front desk area.[31] The coffee shop, which also served small meals and box lunches, was decorated with paintings of Colonial America and was intended to look like an old-fashioned coffee house.[88]

In 1956, with the change in hotel management, the front desk was moved to the north side of the lobby (occupying space previously used for phone booths). The soda fountain and candy shop were eliminated, and the restaurant expanded to occupy the space. The restaurant was renamed the Rib Room.[50][89] When Western International Hotels rook over from HCA, the restaurant lost its name (which was a trademark of HCA). The restaurant was subsequently named The Carvery in July 1972.[90] The Carvery closed in 2004.[91]

The Promenade originally featured pilasters that defined six bays along both its north and south sides. The capital of each pilaster was decorated with the profile of a different mythological hero, and festooned with swag. Each pilaster had a faux pedestal made of verd antique decorated with plaster rosettes and gilt plaster wreaths. The wainscoting was 3 feet (0.91 m) high, and of white Alabama marble. A baseboard of verd antique and a gray marble dado rail completed the wainscot, and a gilt plaster acanthus crown molding decorated the ceiling.

Arches in the north wall gave access to meeting rooms. The arches leading to the Grand Ballroom, Chinese Room, and the original Presidential Room were topped with sculpted architraves of white Alabama marble, while the other arches were each topped by a gilt plaster crest. The arches which led to the small meeting rooms along the north wall were eventually filled in with gilt-edged mirrors. Beveled mirrors stood between the pilasters.

The ceiling of the Promenade consisted of octagonal coffers alternating with small square coffers. At the center of each square coffer was a gilt plaster rosette. The floor was of white Vermont marble and verd antique marble, with a border of verd antique.

Photos Bruce Alan St. Germain

Its Architecture

Beaux-Arts - Louis XV - Early Renaissance

Beaux-Arts

Beaux-Arts architecture was the academic architectural style taught at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, particularly from the 1830s to the end of the 19th century. It drew upon the principles of French neoclassicism, but also incorporated Renaissance and Baroque elements, and used modern materials, such as iron and glass. It was an important style in France until the end of the 19th century.

The Beaux-Arts style evolved from the French classicism of the Style Louis XIV, and then French neoclassicism beginning with Style Louis XV and Style Louis XVI. French architectural styles before the French Revolution were governed by Académie royale d'architecture (1671–1793), then, following the French Revolution, by the Architecture section of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. The Academy held the competition for the Grand Prix de Rome in architecture, which offered prize winners a chance to study the classical architecture of antiquity in Rome.[2]

The formal neoclassicism of the old regime was challenged by four teachers at the Academy, Joseph-Louis Duc, Félix Duban, Henri Labrouste and Léon Vaudoyer, who had studied at the French Academy in Rome at the end of the 1820s. They wanted to break away from the strict formality of the old style by introducing new models of architecture from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Their goal was to create an authentic French style based on French models. Their work was aided beginning in 1837 by the creation of the Commission of Historic Monuments, headed by the writer and historian Prosper Mérimée, and by the great interest in the Middle Ages caused by the publication in 1831 of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame by Victor Hugo. Their declared intention was to "imprint upon our architecture a truly national character."[3]

The style referred to as Beaux-Arts in English reached the apex of its development during the Second Empire (1852–1870) and the Third Republic that followed. The style of instruction that produced Beaux-Arts architecture continued without major interruption until 1968.[2]

The Beaux-Arts style heavily influenced the architecture of the United States in the period from 1880 to 1920.[4] In contrast, many European architects of the period 1860–1914 outside France gravitated away from Beaux-Arts and towards their own national academic centers. Owing to the cultural politics of the late 19th century, British architects of Imperial classicism followed a somewhat more independent course, a development culminating in Sir Edwin Lutyens's New Delhi government buildings.

The Beaux-Arts training emphasized the mainstream examples of Imperial Roman architecture between Augustus and the Severan emperors, Italian Renaissance, and French and Italian Baroque models especially, but the training could then be applied to a broader range of models: Quattrocento Florentine palace fronts or French late Gothic. American architects of the Beaux-Arts generation often returned to Greek models, which had a strong local history in the American Greek Revival of the early 19th century. For the first time, repertories of photographs supplemented meticulous scale drawings and on-site renderings of details.

Beaux-Arts training made great use of agrafes, clasps that link one architectural detail to another; to interpenetration of forms, a Baroque habit; to "speaking architecture" (architecture parlante) in which supposed appropriateness of symbolism could be taken to literal-minded extremes. It also emphasized the production of quick conceptual sketches, highly finished perspective presentation drawings, close attention to the program, and knowledgeable detailing. Site considerations included the social and urban context.[5]

All architects-in-training passed through the obligatory stages—studying antique models, constructing analos, analyses reproducing Greek or Roman models, "pocket" studies and other conventional steps—in the long competition for the few desirable places at the Académie de France à Rome (housed in the Villa Medici) with traditional requirements of sending at intervals the presentation drawings called envois de Rome.

Beaux-Arts architecture had a strong influence on architecture in the United States because of the many prominent American architects who studied at the École des Beaux-Arts, including Henry Hobson Richardson, John Galen Howard, Daniel Burnham, and Louis Sullivan.[9]

The first American architect to attend the École des Beaux-Arts was Richard Morris Hunt, between 1846 and 1855, followed by Henry Hobson Richardson in 1860. They were followed by an entire generation. Richardson absorbed Beaux-Arts lessons in massing and spatial planning, then applied them to Romanesque architectural models that were not characteristic of the Beaux-Arts repertory. His Beaux-Arts training taught him to transcend slavish copying and recreate in the essential fully digested and idiomatic manner of his models. Richardson evolved a highly personal style (Richardsonian Romanesque) freed of historicism that was influential in early Modernism.[10]

The "White City" of the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago was a triumph of the movement and a major impetus for the short-lived City Beautiful movement in the United States.[11] Beaux-Arts city planning, with its Baroque insistence on vistas punctuated by symmetry, eye-catching monuments, axial avenues, uniform cornice heights, a harmonious "ensemble," and a somewhat theatrical nobility and accessible charm, embraced ideals that the ensuing Modernist movement decried or just dismissed.[12] The first American university to institute a Beaux-Arts curriculum is the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 1893, when the French architect Constant-Désiré Despradelle was brought to MIT to teach. The Beaux-Arts curriculum was subsequently begun at Columbia University, the University of Pennsylvania, and elsewhere.[13] From 1916, the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design in New York City schooled architects, painters, and sculptors to work as active collaborators.

Numerous American university campuses were designed in the Beaux-Arts, notably: Columbia University, (commissioned in 1896), designed by McKim, Mead & White; the University of California, Berkeley (commissioned in 1898), designed by John Galen Howard; the United States Naval Academy (built 1901–1908), designed by Ernest Flagg; the campus of MIT (commissioned in 1913), designed by William W. Bosworth; Emory University and Carnegie Mellon University (commissioned in 1908 and 1904, respectively),[14] both designed by Henry Hornbostel; and the University of Texas (commissioned in 1931), designed by Paul Philippe Cret.

While the style of Beaux-Art buildings was adapted from historical models, the construction used the most modern available technology. The Grand Palais in Paris (1897–1900) had a modern iron frame inside; the classical columns were purely for decoration. The 1914–1916 construction of the Carolands Chateau south of San Francisco was built to withstand earthquakes, following the devastating 1906 San Francisco earthquake. The noted Spanish structural engineer Rafael Guastavino (1842–1908), famous for his vaultings, known as Guastavino tile work, designed vaults in dozens of Beaux-Arts buildings in Boston, New York, and elsewhere. Beaux-Arts architecture also brought a civic face to railroads. Chicago's Union Station, Detroit's Michigan Central Station, Jacksonville's Union Terminal, Grand Central Terminal and the original Pennsylvania Station in New York, and Washington, DC's Union Station are famous American examples of this style. Cincinnati has a number of notable Beaux-Arts style buildings, including the Hamilton County Memorial Building in the Over-the-Rhine neighborhood, and the former East End Carnegie library in the Columbia-Tusculum neighborhood.

An ecclesiastical variant on the Beaux-Arts style is Minneapolis' Basilica of St. Mary,[15] the first basilica in the United States, which was designed by Franco-American architect Emmanuel Louis Masqueray (1861–1917) and opened in 1914, and a Freemason temple variant, the Plainfield Masonic Temple, in Plainfield, New Jersey, designed by John E. Minott in 1927. The main branch of the New York Public Library is another prominent example. Another prominent U.S. example of the style is the largest academic dormitory in the world, Bancroft Hall at the abovementioned United States Naval Academy.[16] The tallest railway station in the world at the time of completion, Michigan Central Station in Detroit, was also designed in the style.[17]

In the late 1800s, during the years when Beaux-Arts architecture was at a peak in France, Americans were one of the largest groups of foreigners in Paris. Many of them were architects and students of architecture who brought this style back to America.[18] The following individuals, students of the École des Beaux-Arts, are identified as creating work characteristic of the Beaux-Arts style within the United States:

Evarts Tracy of Tracy and Swartwout

Louis XV

The Louis XV style or Louis Quinze is a style of architecture and decorative arts which appeared during the reign of Louis XV. From 1710 until about 1730, a period known as the Régence, it was largely an extension of the Louis XIV style of his great-grandfather and predecessor, Louis XIV. From about 1730 until about 1750, it became more original, decorative and exuberant, in what was known as the Rocaille style, under the influence of the King's mistress, Madame de Pompadour. It marked the beginning of the European Rococo movement. From 1750 until the King's death in 1774, it became more sober, ordered, and began to show the influences of Neoclassicism.

The chief architect of the King was Jacques Gabriel from 1734 until 1742, and then his more famous son, Ange-Jacques Gabriel, until the end of the reign. His major works included the Ecole Militaire, the ensemble of buildings overlooking the Place Louis XV (now Place de la Concorde; 1761-1770), and the Petit Trianon at Versailles (1764). Over the course of the reign of Louis XV, while interiors were lavishly decorated, the facades gradually became simpler, less ornamented and more classical. The facades designed by Gabriel were carefully rhymed and balanced by rows of windows and columns, and, on large buildings like those surrounding the Place de la Concorde, often featured grand arcades on the street level, and classical pediments or balustrades on the roofline. Ornamental features sometimes included curving wrought-iron balconies with undulating rocaille designs, similar to the rocaille decoration of the interiors.[1]

The religious architecture of the period was also sober and monumental, and it tended, at the end of the reign, toward the neoclassical. Major examples include the Church of Saint-Genevieve (now the Panthéon), built from 1758 to 1790 to a design by Jacques-Germain Soufflot, and the Church of Saint-Philippe-du-Roule (1765-1777) by Jean Chalgrin, which featured an enormous barrel-vaulted nave.[2]

Interior decoration during the reign of Louis XV fell into two periods; the first especially featured rocaille ornament, sculpted sinuous curves and counter-curves, often in floral and vegetative patterns, applied to the panels of the walls, often with medallions in the center. The panels large mirrors were framed in often framed with sculpted palm leaves or other floral decoration. Unlike the rococo style, the ornament was usually restrained, symmetrical and balanced. In the early period of the style, the designs were often inspired by French versions of Chinese art, animals, especially monkeys (Singerie) and arabesques, or themes taken from works of the artists of the period, including Jean Bérain the Younger, Watteau and Jean Audran.[3]

After 1750, in reaction to the excesses of the earlier style, the designs and moldings on the interior walls were white or pale colored, more geometric, decorated with sculpted garlands, roses, and crowns, and ornamented with designs inspired by ancient Greece and Rome. This style was found in the Salon de Compagnie at the Petit Trianon, and it was the predecessor of the Louis XVI style.[4]

Early Renaissance

The Florentine painter Giotto di Bondone developed a manner of figurative painting that was unprecedentedly naturalistic, three-dimensional, lifelike and classicist, when compared with that of his contemporaries and teacher Cimabue. Giotto, whose greatest work is the cycle of the Life of Christ at the Arena Chapel in Padua, was seen by the 16th-century biographer Giorgio Vasari as "rescuing and restoring art" from the "crude, traditional, Byzantine style" prevalent in Italy in the 13th century.

Although Giotto had students and followers, the first truly Renaissance artists were not to emerge in Florence until 1401 with the competition to sculpt a set of bronze doors of the Baptistery of Florence Cathedral, which drew entries from seven young sculptors including Brunelleschi, Donatello and the winner, Lorenzo Ghiberti. Brunelleschi, most famous as the architect of the dome of Florence Cathedral and the Church of San Lorenzo, created a number of sculptural works, including a life-sized crucifix in Santa Maria Novella, renowned for its naturalism. His studies of perspective are thought to have influenced the painter Masaccio. Donatello became renowned as the greatest sculptor of the Early Renaissance, his masterpieces being his humanist and unusually erotic statue of David, one of the icons of the Florentine republic, and his great monument to Gattamelata, the first large equestrian bronze to be created since Roman times.

The contemporary of Donatello, Masaccio, was the painterly descendant of Giotto and began the Early Renaissance in Italian painting in 1425, furthering the trend towards solidity of form and naturalism of face and gesture that Giotto had begun a century earlier. From 1425–1428, Masaccio completed several panel paintings but is best known for the fresco cycle that he began in the Brancacci Chapel with the older artist Masolino and which had profound influence on later painters, including Michelangelo. Masaccio's developments were carried forward in the paintings of Fra Angelico, particularly in his frescos at the Convent of San Marco in Florence.

The treatment of the elements of perspective and light in painting was of particular concern to 15th-century Florentine painters. Uccello was so obsessed with trying to achieve an appearance of perspective that, according to Giorgio Vasari, it disturbed his sleep. His solutions can be seen in his masterpiece set of three paintings, the Battle of San Romano, which is believed to have been completed by 1460. Piero della Francesca made systematic and scientific studies of both light and linear perspective, the results of which can be seen in his fresco cycle of The History of the True Cross in San Francesco, Arezzo.

In Naples, the painter Antonello da Messina began using oil paints for portraits and religious paintings at a date that preceded other Italian painters, possibly about 1450. He carried this technique north and influenced the painters of Venice. One of the most significant painters of Northern Italy was Andrea Mantegna, who decorated the interior of a room, the Camera degli Sposi for his patron Ludovico Gonzaga, setting portraits of the family and court into an illusionistic architectural space.

The end period of the Early Renaissance in Italian art is marked, like its beginning, by a particular commission that drew artists together, this time in cooperation rather than competition. Pope Sixtus IV had rebuilt the Papal Chapel, named the Sistine Chapel in his honour, and commissioned a group of artists, Sandro Botticelli, Pietro Perugino, Domenico Ghirlandaio and Cosimo Rosselli to decorate its wall with fresco cycles depicting the Life of Christ and the Life of Moses. In the sixteen large paintings, the artists, although each working in his individual style, agreed on principles of format, and utilised the techniques of lighting, linear and atmospheric perspective, anatomy, foreshortening and characterisation that had been carried to a high point in the large Florentine studios of Ghiberti, Verrocchio, Ghirlandaio and Perugino.

Photos Bruce Alan St. Germain And The Mayflower Hotel

Its Architectural Characteristics

Beaux-Arts architecture depended on sculptural decoration along conservative modern lines, employing French and Italian Baroque and Rococo formulas combined with an impressionistic finish and realism.

Slightly overscaled details, bold sculptural supporting consoles, rich deep cornices, swags and sculptural enrichments in the most bravura finish the client could afford gave employment to several generations of architectural modellers and carvers of Italian and Central European backgrounds. A sense of appropriate idiom at the craftsman level supported the design teams of the first truly modern architectural offices.

Characteristics of Beaux-Arts architecture included:

Flat roof[4]

Rusticated and raised first story[4]

Hierarchy of spaces, from "noble spaces"—grand entrances and staircases—to utilitarian ones

Arched windows[4]

Arched and pedimented doors[4]

Classical details:[4] references to a synthesis of historicist styles and a tendency to eclecticism; fluently in a number of "manners"

Symmetry[4]

Statuary,[4] sculpture (bas-relief panels, figural sculptures, sculptural groups), murals, mosaics, and other artwork, all coordinated in theme to assert the identity of the building

Classical architectural details:[4] balustrades, pilasters, festoons, cartouches, acroteria, with a prominent display of richly detailed clasps (agrafes), brackets and supporting consoles

Subtle polychromy

Become A Donor Or Advertiser