The Willard InterContinental

Photos Bruce Alan St. Germain

Photos Bruce Alan St. Germain

Its History

The Willard InterContinental is a historic luxury Beaux-Arts[3] hotel located at 1401 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Downtown Washington, DC. The story of The Willard InterContinental begins in 1818 when six row-houses on the corner of 14th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, built by Lt. Colonel John Tayloe III in 1816, are leased to Joshua Tennyson to be used as a hotel. Over the next 30 years both the name of the hotel and it’s operator would change multiple times. The hotel, by then known as the City Hotel, became famous for its signature cocktail when in 1830 Kentucky Statesman Henry Clay first introduced the Mint Julep to Washingtonians in the hotel’s Round Robin Bar.

In 1847 a gentleman named Henry Willard was hired by Benjamin Ogle Tayloe to operate The Willard after years of falling profits. Willard combined them into a single structure, and enlarged it into a four-story hotel he renamed Willard's Hotel.[2][7][8] Willard purchased the hotel property from Ogle Tayloe in 1864, but a dispute over the purchase price and the form of payment (paper currency or gold coin) led to a major equity lawsuit which ended up in the Supreme Court of the United States. The Supreme Court split the difference in Willard v. Tayloe. 75 U.S. 557 (1869): The purchase price would remain the same, but Willard was required to pay in gold coin (which had not depreciated in value the way paper currency had).

In 1853 President Franklin Pierce made the Willard’s City Hotel home, becoming the hotel’s first presidential patron. The hotel gained further fame when in 1859 it hosted the Napier Ball, an extremely lavish event attended by 1,200 notables in honor of British minister Lord Napier.

The hotel’s prominence continued to grow when in 1860 the hotel became selected to house the first ever Japanese Delegation to the United States. Comprised of three Samurai ambassadors and an entourage of seventy-four, the Japanese delegation came to Washington to meet with President James Buchanan with the goal of ratifying the Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation in an effort to build a close relationship between the two nations.

In a last ditch effort to avoid the Civil War, then ex-President John Tyler chaired the historic Peace Convention in 1861 at Willard's City Hotel. That same year President–elect Abraham Lincoln took up residence at the hotel for ten days prior to his inauguration. Upon hearing a Union regiment singing "John Brown's Body" as they marched beneath her window, Julia Ward Howe wrote the lyrics to "The Battle Hymn of the Republic" while staying at the hotel in November 1861.[4]

In the 1860s, author Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote that "the Willard Hotel more justly could be called the center of Washington than either the Capitol or the White House or the State Department."[20]. In 1868 General John A. Logan, while staying at the hotel, issued an order designating May 13, 1868 as a day to observe the memory of those who have fallen in battle, thus beginning the tradition of Memorial Day.

Many United States presidents have frequented the Willard, and every president since Franklin Pierce has either slept in or attended an event at the hotel at least once; the hotel hence is also known as "the residence of presidents."[22] It was the habit of Ulysses S. Grant to drink whiskey and smoke a cigar while relaxing in the lobby. Folklore holds that this is the origin of the term "lobbying," as Grant was often approached by those seeking favors. However, Webster's Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary dates the verb "to lobby" to 1837.

Grover Cleveland lived there at the beginning of his second term in 1893, because of concern for his infant daughter's health following a recent outbreak of scarlet fever in the White House.[23] Plans for Woodrow Wilson's League of Nations took shape when he held meetings of the League to Enforce Peace in the hotel's lobby in 1916. Six sitting Vice-Presidents have lived in the Willard. Millard Fillmore and Thomas A. Hendricks, during his brief time in office, lived in the old Willard; and then four successive Vice-Presidents, James S. Sherman, Thomas R. Marshall, Calvin Coolidge and finally Charles Dawes all lived in the current building for at least part of their vice-presidency. Fillmore and Coolidge continued in the Willard, even after becoming president, to allow the first family time to move out of the White House. It was during this time in which the Presidential flag flew outside the hotel.

The present 12-story structure, designed by famed hotel architect Henry Janeway Hardenbergh, opened in 1901.[3][4] The University Club of Washington was founded in the hotel’s Red Room in 1904 and in 1908 the National Press Club was founded at The Willard. It suffered a major fire in 1922 which caused $250,000 (equivalent to $4,047,217 as of 2021),[9] in damages.[10] Among those who had to be evacuated from the hotel were Vice President Calvin Coolidge, several U.S. senators, composer John Philip Sousa, motion picture producer Adolph Zukor, newspaper publisher Harry Chandler, and numerous other media, corporate, and political leaders who were present for the annual Gridiron Dinner.[10]

The Willard family sold its share of the hotel in 1946, and due to mismanagement and the severe decline of the area. In 1963 Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. sat in the hotel lobby with his closest advisors to make final edits to his famous “I Have a Dream” speech, hours before delivering it on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.

Following years of declining revenue, the April riots of DC, and the proposed Pennsylvania Avenue plan by the President’s Advisory Council which called for the creation of a “National Square” at the western end of the avenue eliminating all of the buildings on the Willard block, the property closed without a prior announcement on July 16, 1968.[11] The United Citizens for Nixon-Agnew leased four floors of the hotel in the fall of 1968 to work for the election of Richard M. Nixon. The following year the hotel’s furniture, fixtures and equipment of the hotel were sold to the public at auction.

The building sat vacant for years, and numerous plans were floated for its demolition. It eventually fell into a semi-public receivership and was sold to the Pennsylvania Avenue Development Corporation. They held a competition to rehabilitate the property and ultimately awarded it to the Oliver Carr Company and Golding Associates.[12] The two partners then brought in the InterContinental Hotels Group to be a part owner and operator of the hotel. The Willard was subsequently restored to its turn-of-the-century elegance and an office-building contingent was added. The hotel was thus re-opened amid great celebration on August 20, 1986, which was attended by several U.S. Supreme Court justices and U.S. senators. In the late 1990s, the hotel once again underwent significant restoration.

The Willard returned to being the prominent residence of society’s most influential. In 1998 22 Finance Ministers from around the world, known as the ‘Group of 22’, met at The Willard to discuss the stability of the international financial markets. Academy Award-winning director, Steven Spielberg and Academy Award-winning actor, Tom Cruise filmed scenes for the movie Minority Report throughout the property in 2001. And in 2003 His Holiness the Dalai Lama attended a conference breakfast meeting at The Willard.

In 2009 The Willard once again witnessed history as Barack Obama, the country’s first African-American U.S. president led his Inaugural Parade past the hotel. Former President Jimmy Carter gave a keynote speech at a conference held at the hotel in 2012. And in 2014 The Willard hosted seven African heads-of-state attending the first ever U.S. – African Leaders Summit.

In 2016 The Willard launched a first-of-its-kind Kids Concierge program. The following year India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi hosted a CEO roundtable in the Ballroom of the Willard InterContinental with twenty-one leaders of America’s top companies. And in 2018 The Willard celebrated its Bicentennial, remembering 200 years as one of the most historic hotels in America.

The Washington Post reported on October 23, 2021 that the hotel was a "command center" for a White House plot to overturn the results of the 2020 election.[13] The Guardian reported that, during the January 5 meeting at the hotel, lawyer John C. Eastman went through his January 4 memo describing his theory that Vice President Mike Pence could refuse to certify certain state elector slates the following day, and hand Trump a second term instead.[14] On November 8, 2021, the United States House Select Committee on the January 6 Attack issued subpoenas to Eastman and five other Trump allies present at the meeting.[15] On November 30, 2021, The Guardian further reported that Trump personally called his lieutenants at the hotel on the night of January 5 to discuss how to delay certification of the election results.[16] On December 27, 2021, the House select committee announced its intention to investigate that phone call.[17]

Photos Bruce Alan St. Germain

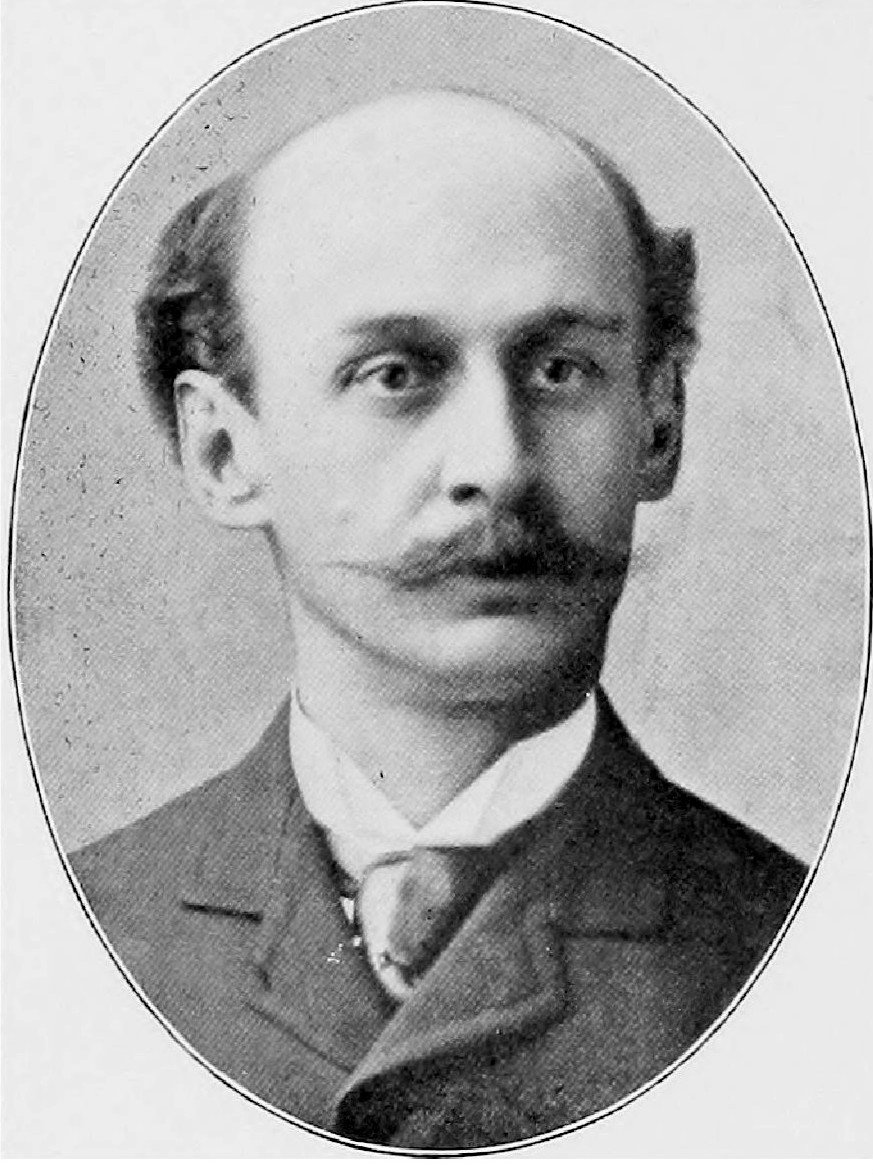

Its Architect

Photo Library Of Congress

Henry Janeway Hardenbergh

1847 - 1918

Henry Janeway Hardenbergh (February 6, 1847 – March 13, 1918) was an American architect, best known for his hotels and apartment buildings, and as a "master of a new building form -- the skyscraper."[2]

Hardenbergh was born in New Brunswick, New Jersey, of a Dutch family, and attended the Hasbrouck Institute in Jersey City. He apprenticed in New York from 1865 to 1870 under Detlef Lienau, and, in 1870, opened his own practice there.[3]

He obtained his first contracts for three buildings at Rutgers College in New Brunswick, New Jersey—the expansion of Alexander Johnston Hall (1871), designing and building Geology Hall (1872) and the Kirkpatrick Chapel (1873)—through family connections. Hardenbergh's great-great grandfather, the Reverend Jacob Rutsen Hardenbergh, had been the first president of Rutgers College from 1785 to 1790, when it was still called "Queen's College".

He then got the contract to design the "Vancorlear" on West 55th Street, the first apartment hotel in New York City, in 1879.[1] The following year he was commissioned by Edward S. Clark, then head of the Singer Sewing Machine Company, to build a housing development. As part of this work, he designed the pioneering Dakota Apartments in Central Park West, novel in its location, very far north of the center of the city.

Subsequently, Hardenbergh received commissions to build the Waldorf (1893) and the adjoining Astoria (1897) hotels for William Waldorf Astor and Mrs. Astor, respectively. The two competing hotels were later joined together as the Waldorf-Astoria, which was demolished in 1929 for the construction of the Empire State Building.

Hardenbergh lived for some time in Bernardsville, New Jersey[4] the town in which he designed the building for the school house built with funds donated by Frederic P. Olcott.[2] The school house is in Hardenberghs architectural style and is a landmark in the town.[5] Hardenbergh died at his home in Manhattan, New York City on March 13, 1918.[1] He is buried in Woodland Cemetery, in Stamford, Connecticut.

Hardenbergh was elected to the American Institute of Architects in 1867, and was made a Fellow in 1877. He was president of the Architectural League of New York from 1901 to 1902, and was an associate of the National Academy of Design. Hardenbergh was one of the founders of the American Fine Arts Society as well as the Municipal Art Society.[3] He was also a member of the Sculpture Society and the Century, Riding, Grolier and Church Clubs.[1]

List Of Architectural Contributions

1870: Addition to the Rutgers Preparatory School building (now Alexander Johnston Hall) in New Brunswick, New Jersey.

1871–1872: library, chapel[1] and Geology Hall, at Rutgers College (now university), in New Brunswick, New Jersey.

1873: Sophia Astley Kirkpatrick Memorial Chapel at Rutgers College, New Brunswick, New Jersey, with windows by Louis Comfort Tiffany (renovated 1916)[6]

1873: Suydam Hall at New Brunswick Theological Seminary in New Brunswick, New Jersey (razed 1966)

1876: Kingfisher Tower near Cooperstown, New York

1878: Windsor Hotel in Montreal[1] (demolished except for North Annex, 1975

1879: The Vancolear, West 55th Street and Seventh Avenue, the city's first apartment hotel[1]

1879: Loch Ada, 590 Proctor Road, Glen Spey, Lumberland, Sullivan County, New York (razed 1996)

1879–1880: two row houses at 101 and 103 West 73rd Street in Manhattan, New York City [7]

1880–1884: The Dakota Apartments located on Manhattan's Upper West Side, in New York City (NYC landmark)[8]

1882–1884: Western Union Telegraph Building, located at 186 Fifth Avenue at 23rd Street in Manhattan, New York City[9]

1882–1885: Several Row houses at 15A-19 and 41-65 West 73rd Street on Manhattan's Upper West Side, New York City[7]

1883: Hotel Albert (now the Albert Apartments) in Manhattan, New York City[7]

1883-84: 1845 Broadway in Manhattan, New York City[10]

1886–1887: 337 & 339 East 87th Street, Manhattan, New York City[11]

1888: Schermerhorn Building at 376-380 Lafayette Street in Manhattan, New York City

1888–1889: Apartment building at 121 East 89th Street part of the Hardenbergh/Rhinelander Historic District [8]

1888–1889: Row houses at 1340, 1342, 1344, 1346, 1348 and 1350 Lexington Avenue part of the Hardenbergh/Rhinelander Historic District [8]

1891–1892: American Fine Arts Society building, home of the Art Students League of New York, in Manhattan, New York City (NYC landmark)[8]

1893: Waldorf Hotel located at 34th Street and Fifth Avenue in Midtown Manhattan, New York City (demolished 1929 to build Empire State Building)

1893: Hotel Manhattan located on the northwest corner of Madison Avenue and 42nd Street in New York City, New York.

1895: Wolfe Building, at William Street and Maiden Lane, New York City (demolished in 1974)

1897: Astoria Hotel located at 34th Street and Fifth Avenue in Midtown Manhattan, New York City (demolished 1929 to build Empire State Building)

1897: William Murray Houses, located at 13 and 15 West 54th Street, Manhattan, New York City (NYC landmark)[8]

1897–1900: Hotel Martinique on Broadway in Manhattan, New York City (enlarged 1907-11)[7] a NYC landmark [8]

1900–1901: Textile Building on Leonard Street and Church Street in Manhattan, New York City (penthouse added in 2001) a NYC landmark [8]

1901: Willard Hotel in Washington, D.C.

1902: Sunnyside Island, in the 1000 Islands, New York

1902–1904: Whitehall Building in Manhattan, New York City (NYC landmark)[8]

1903: Preston B. Moss House, 914 Division St., Billings, Montana

1904: All Angels' Church – Manhattan, New York City

1904: Van Norden Trust Company Building, 751 5th Ave., New York City, demolished.[12]

1905–1907: Plaza Hotel at corner of Fifth Avenue and Central Park South (West 59th Street) in Midtown Manhattan, New York City[13] a NYC landmark [8]

1908: Trinity Episcopal Church in York Harbor, Maine

1910: Palmer Physical Laboratory, at Princeton University[14]

1911: The Raleigh Hotel at 1111 Pennsylvania Avenue, in Washington D.C. (demolished 1965)

1912: Copley Plaza Hotel in Boston, Massachusetts

1912: Stamford Trust Company Building, 300 Main St., Stamford, Connecticut[15]

1914: Palmer Stadium, the football stadium and track arena at Princeton University, in Princeton, New Jersey (demolished 1998)[16]

1915: Consolidated Edison Company Building in Manhattan, New York City (the building only, not the tower)

1917–1918: New Jersey Zinc Company Headquarters, Maiden Lane, Manhattan, New York City.

Photos Bruce Alan St. Gernain

Its Architecture

Beux-Arts

Beaux-Arts architecture was the academic architectural style taught at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, particularly from the 1830s to the end of the 19th century. It drew upon the principles of French neoclassicism, but also incorporated Renaissance and Baroque elements, and used modern materials, such as iron and glass. It was an important style in France until the end of the 19th century.

The Beaux-Arts style evolved from the French classicism of the Style Louis XIV, and then French neoclassicism beginning with Style Louis XV and Style Louis XVI. French architectural styles before the French Revolution were governed by Académie royale d'architecture (1671–1793), then, following the French Revolution, by the Architecture section of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. The Academy held the competition for the Grand Prix de Rome in architecture, which offered prize winners a chance to study the classical architecture of antiquity in Rome.[2]

The formal neoclassicism of the old regime was challenged by four teachers at the Academy, Joseph-Louis Duc, Félix Duban, Henri Labrouste and Léon Vaudoyer, who had studied at the French Academy in Rome at the end of the 1820s. They wanted to break away from the strict formality of the old style by introducing new models of architecture from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Their goal was to create an authentic French style based on French models. Their work was aided beginning in 1837 by the creation of the Commission of Historic Monuments, headed by the writer and historian Prosper Mérimée, and by the great interest in the Middle Ages caused by the publication in 1831 of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame by Victor Hugo. Their declared intention was to "imprint upon our architecture a truly national character."[3]

The style referred to as Beaux-Arts in English reached the apex of its development during the Second Empire (1852–1870) and the Third Republic that followed. The style of instruction that produced Beaux-Arts architecture continued without major interruption until 1968.[2]

The Beaux-Arts style heavily influenced the architecture of the United States in the period from 1880 to 1920.[4] In contrast, many European architects of the period 1860–1914 outside France gravitated away from Beaux-Arts and towards their own national academic centers. Owing to the cultural politics of the late 19th century, British architects of Imperial classicism followed a somewhat more independent course, a development culminating in Sir Edwin Lutyens's New Delhi government buildings.

The Beaux-Arts training emphasized the mainstream examples of Imperial Roman architecture between Augustus and the Severan emperors, Italian Renaissance, and French and Italian Baroque models especially, but the training could then be applied to a broader range of models: Quattrocento Florentine palace fronts or French late Gothic. American architects of the Beaux-Arts generation often returned to Greek models, which had a strong local history in the American Greek Revival of the early 19th century. For the first time, repertories of photographs supplemented meticulous scale drawings and on-site renderings of details.

Beaux-Arts training made great use of agrafes, clasps that link one architectural detail to another; to interpenetration of forms, a Baroque habit; to "speaking architecture" (architecture parlante) in which supposed appropriateness of symbolism could be taken to literal-minded extremes.

Beaux-Arts training emphasized the production of quick conceptual sketches, highly finished perspective presentation drawings, close attention to the program, and knowledgeable detailing. Site considerations included the social and urban context.[5]

All architects-in-training passed through the obligatory stages—studying antique models, constructing analos, analyses reproducing Greek or Roman models, "pocket" studies and other conventional steps—in the long competition for the few desirable places at the Académie de France à Rome (housed in the Villa Medici) with traditional requirements of sending at intervals the presentation drawings called envois de Rome.

Beaux-Arts architecture had a strong influence on architecture in the United States because of the many prominent American architects who studied at the École des Beaux-Arts, including Henry Hobson Richardson, John Galen Howard, Daniel Burnham, and Louis Sullivan.[9]

The first American architect to attend the École des Beaux-Arts was Richard Morris Hunt, between 1846 and 1855, followed by Henry Hobson Richardson in 1860. They were followed by an entire generation. Richardson absorbed Beaux-Arts lessons in massing and spatial planning, then applied them to Romanesque architectural models that were not characteristic of the Beaux-Arts repertory. His Beaux-Arts training taught him to transcend slavish copying and recreate in the essential fully digested and idiomatic manner of his models. Richardson evolved a highly personal style (Richardsonian Romanesque) freed of historicism that was influential in early Modernism.[10]

The "White City" of the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago was a triumph of the movement and a major impetus for the short-lived City Beautiful movement in the United States.[11] Beaux-Arts city planning, with its Baroque insistence on vistas punctuated by symmetry, eye-catching monuments, axial avenues, uniform cornice heights, a harmonious "ensemble," and a somewhat theatrical nobility and accessible charm, embraced ideals that the ensuing Modernist movement decried or just dismissed.[12] The first American university to institute a Beaux-Arts curriculum is the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 1893, when the French architect Constant-Désiré Despradelle was brought to MIT to teach. The Beaux-Arts curriculum was subsequently begun at Columbia University, the University of Pennsylvania, and elsewhere.[13] From 1916, the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design in New York City schooled architects, painters, and sculptors to work as active collaborators.

Numerous American university campuses were designed in the Beaux-Arts, notably: Columbia University, (commissioned in 1896), designed by McKim, Mead & White; the University of California, Berkeley (commissioned in 1898), designed by John Galen Howard; the United States Naval Academy (built 1901–1908), designed by Ernest Flagg; the campus of MIT (commissioned in 1913), designed by William W. Bosworth; Emory University and Carnegie Mellon University (commissioned in 1908 and 1904, respectively),[14] both designed by Henry Hornbostel; and the University of Texas (commissioned in 1931), designed by Paul Philippe Cret.

While the style of Beaux-Art buildings was adapted from historical models, the construction used the most modern available technology. The Grand Palais in Paris (1897–1900) had a modern iron frame inside; the classical columns were purely for decoration. The 1914–1916 construction of the Carolands Chateau south of San Francisco was built to withstand earthquakes, following the devastating 1906 San Francisco earthquake. The noted Spanish structural engineer Rafael Guastavino (1842–1908), famous for his vaultings, known as Guastavino tile work, designed vaults in dozens of Beaux-Arts buildings in Boston, New York, and elsewhere.

Beaux-Arts architecture also brought a civic face to railroads. Chicago's Union Station, Detroit's Michigan Central Station, Jacksonville's Union Terminal, Grand Central Terminal and the original Pennsylvania Station in New York, and Washington, DC's Union Station are famous American examples of this style. Cincinnati has a number of notable Beaux-Arts style buildings, including the Hamilton County Memorial Building in the Over-the-Rhine neighborhood, and the former East End Carnegie library in the Columbia-Tusculum neighborhood.

An ecclesiastical variant on the Beaux-Arts style is Minneapolis' Basilica of St. Mary,[15] the first basilica in the United States, which was designed by Franco-American architect Emmanuel Louis Masqueray (1861–1917) and opened in 1914, and a Freemason temple variant, the Plainfield Masonic Temple, in Plainfield, New Jersey, designed by John E. Minott in 1927. The main branch of the New York Public Library is another prominent example. Another prominent U.S. example of the style is the largest academic dormitory in the world, Bancroft Hall at the abovementioned United States Naval Academy.[16] The tallest railway station in the world at the time of completion, Michigan Central Station in Detroit, was also designed in the style.[17]

In the late 1800s, during the years when Beaux-Arts architecture was at a peak in France, Americans were one of the largest groups of foreigners in Paris. Many of them were architects and students of architecture who brought this style back to America.[18] The following individuals, students of the École des Beaux-Arts, are identified as creating work characteristic of the Beaux-Arts style within the United States:

Evarts Tracy of Tracy and Swartwout

Photos Bruce Alan St. Gernain

Second Empire

Second Empire style, also known as the Napoleon III style, was a highly eclectic style of architecture and decorative arts, which used elements of many different historical styles, and also made innovative use of modern materials, such as iron frameworks and glass skylights. It flourished during the reign of Emperor Napoleon III in France (1852–1871) and had an important influence on architecture and decoration in the rest of Europe and North America. Major examples of the style include the Opéra Garnier (1862–1871) in Paris by Charles Garnier, the Bibliothèque nationale de France, the Church of Saint Augustine (1860–1871), and the Philadelphia City Hall. The architectural style was closely connected with Haussmann's renovation of Paris carried out during the Second Empire; the new buildings, such as the Opéra, were intended as the focal points of the new boulevards.

Second Empire is an architectural style most popular in the latter half of the 19th century and early years of the 20th century. It was so named for the architectural elements in vogue during the era of the Second French Empire.[5] As the Second Empire style evolved from its 17th-century Renaissance foundations, it acquired a mix of earlier European styles, most notably the Baroque, often combined with mansard roofs and/or low, square-based domes.[6]

The style quickly spread and evolved as Baroque Revival architecture throughout Europe and across the Atlantic. Its suitability for super-scaling allowed it to be widely used in the design of municipal and corporate buildings. In the United States, where one of the leading architects working in the style was Alfred B. Mullett, buildings in the style were often closer to their 17th-century roots than examples of the style found in Europe.[7]

The dominant architectural style of the Second Empire was eclecticism, drawing liberally from the Gothic style, Renaissance style, and the styles dominant during the reigns of Louis XV and Louis XVI. The style was described by Émile Zola, not an admirer of the Empire, as "the opulent bastard child of all the styles".[8] The best example was the Opéra Garnier, begun in 1862 but not finished until 1875. The architect was Charles Garnier (1825–1898), who won the competition for the design when he was only thirty-seven. When asked by the Empress Eugénie what the style of the building was called, he replied simply, "Napoleon III". At the time, it was the largest opera house in the world, but much of the interior space was devoted to purely decorative spaces: grand stairways, huge foyers for promenading, and large private boxes. Another example was the Mairie, or city hall, of the 1st arrondissement of Paris, built in 1855–1861 in a neo-Gothic style by the architect Jacques Ignace Hittorff (1792–1867).[9]

The Industrial Revolution was beginning to demand a new kind of architecture: bigger, stronger and less expensive. The new age of railways and the enormous increase in travel that it caused required new train stations, large hotels, exposition halls and department stores in Paris. While the exteriors of most Second Empire monumental buildings usually remained eclectic, a revolution was taking place inside; based on the model of The Crystal Palace in London (1851), Parisian architects began to use cast iron frames and walls of glass in their buildings.[10]

The most dramatic use of iron and glass was in the new central market of Paris, Les Halles (1853–1870), an ensemble of huge iron and glass pavilions designed by Victor Baltard (1805–1874) and Félix-Emmanuel Callet (1792–1854). Jacques-Ignace Hittorff also made extensive use of iron and glass in the interior of the new Gare du Nord train station (1842–1865), although the façade was perfectly neoclassical, decorated with classical statues representing the cities served by the railway. Baltard also used a steel frame in building the largest new church to be built in Paris during the Empire, the Church of Saint Augustine (1860–1871). While the structure was supported by cast iron columns, the façade was eclectic. Henri Labrouste (1801–1875) also used iron and glass to create a dramatic cathedral-like reading room for the National Library, Richelieu site (1854–1875).[11]

A mansard or mansard roof (also called a French roof or curb roof) is a four-sided gambrel-style hip roof characterised by two slopes on each of its sides with the lower slope, punctured by dormer windows, at a steeper angle than the upper. The greatest virtue of the mansard is that it can allow an extra full story of space without raising the height of the formal facade, which stops at the entablature. This allowed Parisian architects to gain an additional floor without violating Paris' height restriction.

Massing is a term in architecture which refers to the perception of the general shape and form as well as size of a building. Second Empire architecture was known for its elaborate ornament and strong massing.

The Second Empire also saw the completion or restoration of several architecture treasures: the Nouveau Louvre project realized a longstanding ambition of rationalizing the Louvre Palace, the famed stained glass windows and structure of the Sainte-Chapelle were restored by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, and the Cathedral of Notre-Dame underwent extensive restoration. In the case of the Louvre in particular, the restorations were sometimes more imaginative than precisely historical.

During the Second Empire, under the influence particularly of the architect and historian Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, French religious architecture finally broke away from the neoclassical style which had dominated Paris church architecture since the 18th century. Neo-Gothic and other historical styles began to be built, particularly in the eight new arrondissements farther from the center added by Napoleon III in 1860. The first neo-Gothic church was the Basilica of Sainte-Clothilde, begun by Christian Gau in 1841 and finished by Théodore Ballu in 1857.

During the Second Empire, architects began to use metal frames combined with the Gothic style: the Eglise Saint-Laurent, a 15th-century church rebuilt in neo-Gothic style by Simon-Claude-Constant Dufeux (1862–65), Saint-Eugene-Sainte-Cecile by Louis-Auguste Boileau and Adrien-Louis Lusson (1854–55), and Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Belleville by Jean-Bapiste Lassus (1854–59). The largest new church built in Paris during the Second Empire was Church of Saint Augustine (1860–71) by Victor Baltard, the designer of the metal pavilions of the market of Les Halles. While the façade was eclectic, the structure inside was modern, supported by slender cast iron columns.[12]

Not all churches under Napoleon III were built in the Gothic style. Marseille Cathedral, constructed from 1852 to 1896, was designed in a Byzantine Revival style from 1852 to 1896, principally by Léon Vaudoyer and Henri-Jacques Espérandieu.

Napoleon III's many projects included the completion of the Louvre Palace, which adjoined his own residence in the Tuileries Palace. The Nouveau Louvre project was led by architect Hector Lefuel between 1852 and 1857. Between 1864 and 1868, Napoleon III also commissioned Lefuel to rebuild the Pavillon de Flore; Lefuel added many of his own decorations and ideas to the pavilion, including a celebrated sculpture of Flore by Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux. Lefuel's grands guichets of the Louvre originally featured an equestrian statue of Napoleon III by Antoine-Louis Barye over the central arch, which was removed during the Third Republic.[13]

Comfort was the first priority of Second Empire furniture. Chairs were elaborately upholstered with fringes, tassels, and expensive fabrics. Tapestry work on furniture was very much in style. The structure of chairs and sofas was usually entirely hidden by the upholstery or ornamented with copper, shell, or other decorative elements. Novel and exotic new materials, such as bamboo, papier-mâché, and rattan, were used for the first time in European furniture, along with polychrome wood, and wood painted with black lacquer. The upholstered pouffe, or footstool, appeared, along with the angle sofa and unusual chairs for intimate conversations between two persons (Le confident) or three people (Le indiscret). The crapaud (or toad) armchair was low, with a thickly padded back and arms, and a fringe that hid the legs of the chair.

The French Renaissance and the Henry II style were popular influences on chests and cabinets, buffets and credences, which were massive and built like small cathedrals, decorated with columns, frontons, cartouches, mascarons, and carved angels and chimeras. They were usually constructed of walnut or oak, or sometimes of poirier stained to resemble ebony.[14]

Another popular influence was the Louis XVI style, or French neoclassicism, which was preferred by the Empress Eugénie. Her rooms at the Tuileries Palace and other palaces were decorated in this style.

The Napoleon III style is inseparable from renovation of Paris under Georges-Eugène Haussmann, the Emperor's Prefect of the Seine between 1852 and 1870. The buildings of the renovation show a singularity of purpose and design, a consistency of urban planning that was unusual for the period. Numerous public edifices: railway stations, the tribunal de commerce de Paris, and the Palais Garnier were constructed in the style. The major buildings, including the Opera House and the St. Augustine church, were designed to be the focal points of the new avenues, and to be visible at a great distance.

Another principle characteristic of Second Empire was polychromy, an abundance of color obtained by using colored marble, malachite, onyx, porphyry, mosaics, and silver or gold plated bronze.

Wood panelling was often encrusted with rare and exotic woods, or darkened to resemble ebony.

Napoleon III also built monumental fountains to decorate the heart of the city; his Paris city architect, Gabriel Davioud, designed the polychrome Fontaine Saint-Michel (officially the Fontaine de la Paix) at the beginning of Haussmann's new Boulevard Saint-Michel. Davioud's other major Napoleon III works included the two theatres at the Place du Châtelet, as well as the ornamental fence of Parc Monceau and the kiosks and temples of the Bois de Boulogne, Bois de Vincennes, and other Paris parks.

The expansion of the city limits by Napoleon III and Haussmann's new boulevards called for the construction of a variety of new public buildings, including the new tribunal de commerce (1861–67), influenced by the French Renaissance style, by Théodore Ballu; and the new city hall of the 1st arrondissement, by Jacques Ignace Hittorff (1855–60), in a combination of Renaissance and Gothic styles. The new city hall was located next to the Gothic church of Saint-Germain l'Auxerrois. Between the two structures, the architect Théodore Ballu constructed a Gothic bell tower (1862), to link the two buildings.[15]

New types of architecture connected with the economic expansion: railroad stations, hotels, office buildings, department stores and exposition halls, occupied the center of Paris, which previously had been largely residential. To improve traffic circulation and bring light and air to the center of the city, Napoleon's Prefect of the Seine destroyed the crumbling and overcrowded neighborhoods in the heart of the city and built a network of grand boulevards. The expanded use of new building materials, especially iron frames, allowed the construction of much larger buildings for commerce and industry.[16]

Second Empire, in the United States and Canada, is an architectural style most popular between 1865 and 1900. It was characterized by a mansard roof, elaborate ornament, and strong massing and was notably used for public buildings as well as commercial and residential design. In the 19th century, the standard way to refer to this style of architecture was simply "French" or "Modern French", but later authors came up with the term "Second Empire". Currently, the style is most widely known as Second Empire,[1] Second Empire Baroque,[2] or French Baroque Revival;[3] Leland M. Roth refers to it as "Second Empire Baroque."[4] Mullett-Smith terms it the "Second Empire or General Grant style" due to its popularity in designing government buildings during the Grant administration.[5]

The mansard roof, a defining feature of Second Empire design, had evolved since the 16th century in France and Germany and was often employed in 18th- and 19th-century European architecture. Its appearance in the US was comparatively uncommon in the 18th and early 19th centuries (Mount Pleasant in Philadelphia has an example of early mansard roofs on its side pavilions). In Canada, because of French influence in Quebec and Montreal, the mansard roof was more commonly seen in the 18th century and used as a design feature and never entirely fell out of favor.[7] The earliest Second Empire style private residence in English Canada that was built with a mansard roof was for the commercial druggist and land speculator Tristram Bickle between 1850-55.[8]

It was not until the mid-nineteenth century that the origin of Second Empire architecture in the United States and Canada can be found. A series of major projects and events in French urban planning and design provided the inspiration for Second Empire architecture. Haussmann's renovation of Paris under Napoleon III in the 1850s and the creation of baroque architectural ensembles employing mansard roofs and elaborate ornament provided the impetus for the development and emulation of the style in the US. Haussmann's work was targeted to renovating the decaying Medieval neighborhoods of Paris by wholesale demolition and new construction of streetscapes with uniform cornice lines and stylistic consistency, an urban ensemble that impressed 19th century architects and designers.

The reconstruction of the Louvre Palace between 1852 and 1857 by architects Louis Visconti and Hector Lefuel was widely publicized and served to provide a vocabulary of elaborate baroque architectural ornament for the new style.[9] Finally, the Exposition Universelle of 1855 drew tourists and visitors to Paris and displayed the new architecture and urbanism of the city, an event that brought the style to international attention. These developments worked together to excite interest in design under the Second Empire in the US, particularly among francophiles and those interested in French fashion, then under the sway of Empress Eugenie whose tastes influenced clothing, furniture, and interior decoration.[10] Despite the historicism of the ornamentation, Second Empire architecture was generally viewed as "modern" and hygienic as opposed to the revival styles of Italianate and Gothic Revival which hearkened to the Renaissance and Middle Ages.[11]

The European born and trained architect Detlef Lienau, who studied architecture in Paris and emigrated to the US in 1848, is credited with designing the first Second Empire house in the US, the Hart M. Schiff house in New York City, built in 1850.[12] Lienau remained a prime designer of Second Empire houses, designing the Lockwood-Matthews Mansion in Norwalk, Connecticut (designed 1860). Despite Lienau's work, Second Empire did not displace dominant styles of the 1850s, Italianate and Gothic Revival and remained associated with only particularly wealthy patrons.

Second Empire plans for public buildings are almost entirely cubic or rectangular, adapted from formal French architectural ensembles,

A secondary feature is the use of pavilions, a segment of the facade that is differentiated from surrounding segments by a change in height, stylistic features, or roof design and are typically advanced from the main plane of the facade.

Typical features include quoins at the corners to define elements, elaborate dormer windows, pediments, brackets, and strong entablatures.

A baluster is a vertical moulded shaft, square, or lathe-turned form found in stairways, parapets, and other architectural features. Common materials used in its construction are wood, stone, and less frequently metal and ceramic. A group of balusters supporting a handrail, coping, or ornamental detail are known as a balustrade.

The first major Second Empire structure designed by an American architect was James Renwick's gallery, now the Renwick Gallery designed for William Wilson Corcoran (1859-1860). Renwick's gallery was one of the first major public buildings in the style, and its favorable reception furthered interest in Second Empire design.[13] These early buildings display a close affinity to the high-style designs found in the new Louvre construction, with quoins, stone detailing, carved elements and sculpture, a strong division between base and piano nobile, pavilioned roofs, and pilasters.

The outbreak of the Civil War limited new construction in the US, and it was after the end of the war that Second Empire finally came to prominence in American design. The architects Alfred B. Mullett, who was supervising architect for the Treasury Department, and John McArthur, Jr. a major designer of public buildings in the Mid-Atlantic, helped popularize the style for public and institutional buildings. Mullet, in particular, who favored the style, was responsible from 1866 to 1874 for designing federal public buildings across the US, spreading Second Empire as a stylistic idiom across the country.

His massive and expensive public buildings in St. Louis, Boston, Philadelphia, Cincinnati, New York, and Washington D.C., which closely followed the precedents set by the Louvre construction with grand mansard roofs and tiers of superimposed columns, made a strong impression on the architects in cities with new Mullett designs. Because of its first major appearance in public buildings, Second Empire quickly became the dominant style for the construction of large public projects and commercial buildings.[14] Ironically, buildings in the style built in the US were often closer to their 17th-century roots than examples of the style found in Europe.[15]

Because of the expense of designing buildings with the level of elaborate detailing found in European and public examples, Second Empire residential architecture was first taken up by wealthy businessmen. Since the Civil War had caused a boom in the fortunes of businessmen in the north, Second Empire was considered the perfect style to demonstrate their wealth and express their new power in their respective communities. The style diffused by the publications of designs in pattern books and adopted the adaptability and eclecticism that Italianate architecture had when interpreted by more middle-class clients.[16] This caused more modest homes to depart from the ornamentation found in French examples in favor of simpler and more eclectic American ornamentation that had been established in the 1850s.

In practice, most Second Empire houses simply followed the same patterns developed by Alexander Jackson Davis and Samuel Sloan, the symmetrical plan, the L-plan, for the Italianate style, adding a mansard roof to the composition. Thus, most Second Empire houses exhibited the same ornamentational and stylistic features as contemporary Italianate forms, differing only in the presence or absence of a mansard roof. Second Empire was also a frequent choice of style for remodeling older houses. Frequently, owners of Italianate, Colonial, or Federal houses chose to add a mansard roof and French ornamental features to update their homes in the latest fashions.[17]

As American and Canadian architects went to study in Paris at the École des Beaux-Arts in increasing numbers, Second Empire became more significant as a stylistic choice. Canadian architects benefitted from having a large francophone population in the province of Québec that had for centuries been educated in French styles, as exemplified by the Grand Séminare (1668-1932) with its late Renaissance French colonial design (Québec City). Among the buildings of the American architects that travelled to Paris, the architect H.H. Richardson designed several of his early residences in the style, "evidence of his French schooling".[18] These projects include the Crowninshield House (1868) in Boston Massachusetts, the H. H. Richardson House (1868) in Staten Island, New York, and the William Dorsheimer House (1868) in Buffalo, New York.

Chateau-sur-Mer, on Bellevue Avenue, in Newport, Rhode Island, was remodeled and redecorated during the gilded age of the 1870s by Richard Morris Hunt in this style. This study, however, along with historical events, proved to be the undoing of the style, although Second Empire buildings continued to be constructed until the end of the 19th century. The fall of Napoleon III and the Second Empire in 1870 and the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War soured interest in French styles and taste. Additionally, in the US, Alfred Mullett's extravagance in his designs, waste of money, and the scandal of his association with corrupt businessmen, led to his resignation in 1874 from his post as supervising architect, a development that damaged the style's reputation.[19] Finally, as more architects spent time in Paris among the prime examples of French architecture, their style shifted in favor of a closer fidelity to contemporary French designs, leading to the development of Beaux Arts Classicism in the US.

Second Empire was succeeded by the revival of the Queen Anne Style and its sub-styles, which enjoyed great popularity until the beginning of the "Revival Era" in American architecture just before the end of the 19th century, popularized by the architecture at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893.

Photos Bruce Alan St. Germain

Its Architectural Characteristics

Beaux-Arts

Beaux-Arts architecture depended on sculptural decoration along conservative modern lines, employing French and Italian Baroque and Rococo formulas combined with an impressionistic finish and realism.

Slightly overscaled details, bold sculptural supporting consoles, rich deep cornices, swags and sculptural enrichments in the most bravura finish the client could afford gave employment to several generations of architectural modellers and carvers of Italian and Central European backgrounds. A sense of appropriate idiom at the craftsman level supported the design teams of the first truly modern architectural offices.

Characteristics of Beaux-Arts architecture included:

Flat roof[4]

Rusticated and raised first story[4]

Hierarchy of spaces, from "noble spaces"—grand entrances and staircases—to utilitarian ones

Arched windows[4]

Arched and pedimented doors[4]

Classical details:[4] references to a synthesis of historicist styles and a tendency to eclecticism; fluently in a number of "manners"

Symmetry[4]

Statuary,[4] sculpture (bas-relief panels, figural sculptures, sculptural groups), murals, mosaics, and other artwork, all coordinated in theme to assert the identity of the building

Classical architectural details:[4] balustrades, pilasters, festoons, cartouches, acroteria, with a prominent display of richly detailed clasps (agrafes), brackets and supporting consoles

Subtle polychromy

Another frequent feature is a strong horizontal definition of the facade, with a strong string course. A course is a layer of the same unit running horizontally in a wall. It can also be defined as a continuous row of any masonry unit such as bricks, concrete masonry units (CMU), stone, shingles, tiles, etc.

The three orders of architecture—the Doric (seen here), Ionic, and Corinthian—originated in Greece. The Composit order is a mixed order, combining the volutes of the Ionic order capital with the acanthus leaves of the Corinthian order.

The use of multiple orders in the same structure was common as seen here with the placement of Ionic columns and capitals. Some Second Empire buildings have cast iron facades and elements.

Second Empire

The Napoleon III or Second Empire style took its inspiration from several different periods and styles, which were often combined in the same building or interior. The interior of the Opéra Garnier by Charles Garnier combined architectural elements of the French Renaissance, Palladian architecture, and French Baroque, and managed to give it coherence and harmony. The Lions Gate of the Louvre Palace by Hector Lefuel is a Louis-Napoléon version of French Renaissance architecture; few visitors to the Louvre realize it is a 19th-century addition to the building.[1]

Another characteristic of Napoleon III style is the adaptation of the design of the building to its function and the characteristics of the material used. Examples include the Gare du Nord railway station by Jacques Ignace Hittorff, the Church of Saint Augustin by Victor Baltard, and particularly the iron-framed structures of the market of Les Halles and the reading room of the Bibliothèque nationale in Paris, both also by Victor Baltard.[2]

A basic principle of Napoleon III interior decoration was leave no space undecorated. Another principle was polychromy, an abundance of color obtained by using colored marble, malachite, onyx, porphyry, mosaics, and silver or gold plated bronze. Wood panelling was often encrusted with rare and exotic woods, or darkened to resemble ebony.[3] The façade of the Opéra Garnier employed seventeen different colored materials, including various marbles, stones, and bronze.[4]

The central feature of the Second Empire style is the mansard roof, a four-sided gambrel roof with a shallow or flat top usually pierced by dormer windows. This roof type originated in 16th century France and was fully developed in the 17th century by Francois Mansart, after whom it is named. The greatest virtue of the mansard is that it can allow an extra full story of space without raising the height of the formal facade, which stops at the entablature. The mansard roof can assume many different profiles, with some being steeply angled, while others are concave, convex, or s-shaped. Sometimes mansards with different profiles are superimposed upon one another, especially on towers. For most Second Empire buildings, the mansard roof is the primary stylistic feature and the most commonly recognised link to the style's French roots.

A secondary feature is the use of pavilions, a segment of the facade that is differentiated from surrounding segments by a change in height, stylistic features, or roof design and are typically advanced from the main plane of the facade. Pavilions are usually located at emphatic points in a building such as the center or ends and allow the monotony of the roof to be broken for dramatic effect. While not all Second Empire buildings feature pavilions, a significant number, particularly those built by wealthy clients or as public buildings, do. The Second Empire style frequently includes a rectangular (sometimes octagonal) tower as well. This tower element may be of equal height to the highest floor, or may exceed the height of the rest of the structure by a story or two.

A third feature is massing. Second Empire buildings, because of their height, tend to convey a sense of largeness. Additionally, the facades are typically solid and flat, rather than pierced by open porches or angled and curved facade bays. Public buildings constructed in the Second Empire style were especially built on a massive scale, such as the Philadelphia City Hall and the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, and held records for the largest buildings in their day. Prior to the construction of the Pentagon during the 1940s, for example, the Second Empire–style Ohio State Asylum for the Insane in Columbus, Ohio, was reported to be the largest building under one roof in the U.S., though the title may actually belong to Greystone Park Psychiatric Hospital, another Kirkbride Second Empire asylum.

Second Empire plans for public buildings are almost entirely cubic or rectangular, adapted from formal French architectural ensembles, such as the Louvre. Sometimes they include interior courts. Most Second Empire domestic plans are adapted from prevailing plan types developed for Italianate designs by authors such as Alexander Jackson Davis and Samuel Sloan. The prime distinction between the designs is a preference for a central focus rather than a diffusion of forms. Floor plans for Second Empire residences can be symmetrical, with the tower (or tower-like element) in the center, or asymmetrical, with the tower or tower-like element to one side. Virginia and Lee McAlester divided the style into five subtypes:[6]

Simple mansard roof – about 20%

Centered wing or gable (with bays jutting out at either end)

Asymmetrical – about 20%

Central tower (incorporating a clock) – about 30%

Town house

There are two variations of Second Empire ornamentation: the high style, which followed French precedents closely and employed rich ornamentation, and the more vernacular styles, which lack a strongly distinctive ornamental vocabulary. The high style is mostly seen in expensive public buildings and the houses of the wealthy, while the vernacular form is more common in typical domestic architecture. The exterior style could be expressed in either wood, brick or stone, though high style examples on the whole prefer stone facades or brick facades with stone details (a brick and brownstone combination seems to be particularly common). Some Second Empire buildings have cast iron facades and elements.

High-style Second Empire buildings took their ornamental cue from the Louvre expansion. Typical features include quoins at the corners to define elements, elaborate dormer windows, pediments, brackets, and strong entablatures. There is a clear preference for a variation between rectangular and segmental arched windows; these are frequently enclosed in heavy frames (either arched or rectangular) with sculpted details. Another frequent feature is a strong horizontal definition of the facade, with a strong string course. Particularly high-style examples follow the Louvre precedent by breaking up the facade with superimposed columns and pilasters that typically vary their order between stories. Vernacular buildings typically employed less and more eclectic ornament than high-style specimens that generally followed the vernacular development in other styles.

The mansard roof ridge was frequently topped with a decorative iron trim, known as "cresting". Often, lightning rods were integrated into the cresting, as pinnacles.

Become A Donor Or Advertiser